Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

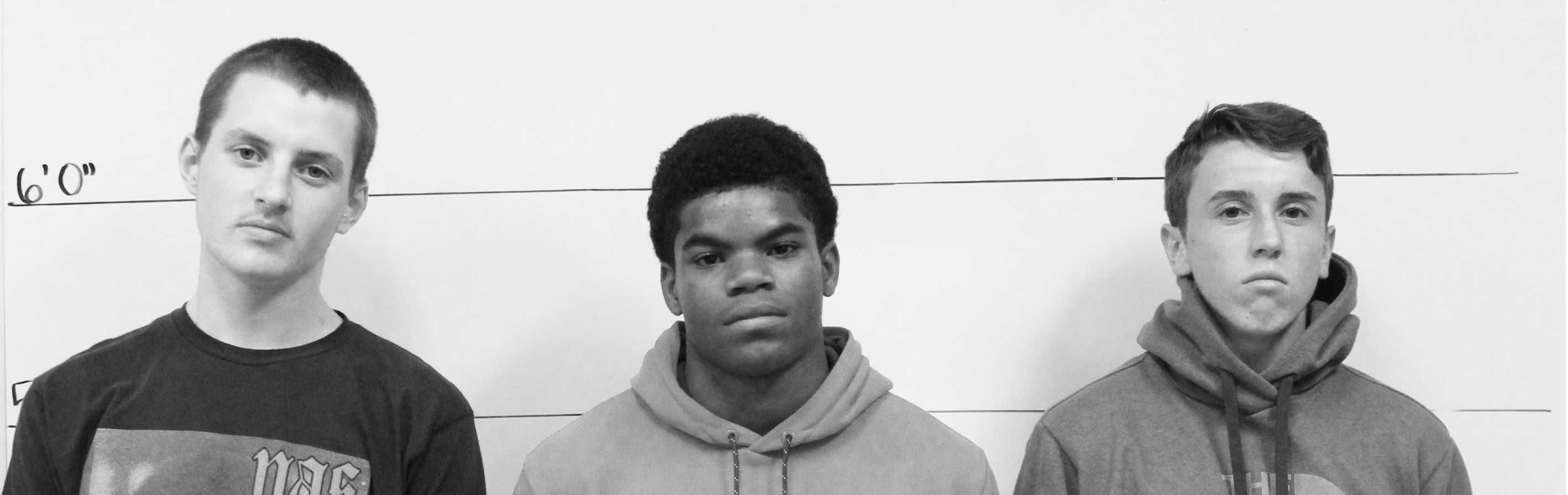

Profiled

Over a month and a half has passed since the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The shooting of the unarmed African American teenager by Darren Wilson, a local police officer, led to riots and peaceful protests against racial profiling and the militarization of the Ferguson law enforcement. This case, along with the Trayvon Martin incident and other cases in recent times, has brought to light the controversial issue of racial profiling, forcing our society to confront it.

September 26, 2014

In Our Nation

After his visit to St. Louis, Missouri in 2004, University of Iowa history professor Colin Gordon became interested in racial dynamics in the area, hoping to answer questions and calm the confusion about racial profiling found among many citizens in both Missouri and other parts of the country alike.

Ever since his visit, Gordon has been tracking changes in populations by race from the mid-1900s through present day. In light of the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, located just outside of St. Louis, his work is especially relevant.

He has documented his studies in his book, Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City, which discusses many ideas about how racial segregation was first established. The inspiration for his book came from his first day in the city.

“I walked out the door and my jaw hit the ground,” Gordon said. “There were beautiful three-story brick houses that were just completely abandoned.”

That curiosity left Gordon begging for more information about how this city could have abandoned itself. Over the next few years he began tracking racial populations in the St. Louis area.

“I think the story is a fairly simple one,” Gordon said. “From the 1940s through 1960s, the city of St. Louis was having issues raising money to pay for school, their factories are going out of business, the city in general is struggling financially.”

Because of the financial devastation and resulting poor living conditions, people started to leave the city.

“There were restrictions on African Americans about where they could and couldn’t live,” Gordon said. “So what happened is that all the whites left Ferguson and went to St. Louis, but blacks had to stay.”

According to Gordon’s research, the 1970s were when the rules began to loosen. It became much easier for African Americans to access insurance and home mortgages.

“About a generation later, once the new rules are in place, black families are able to leave the city and flood into inner suburbs, and when this happens the whites begin to move out,” he said.

This pattern of racial migration is something Gordon predicts will continue to occur. It was also the first thing he thought about after hearing that the death of Michael Brown had occurred in Ferguson.

“Clearly my mind went straight to all the tension in Ferguson,” Gordon said. “All the more so because it’s at that point right now where the population is majority black, and all of their policing and authorities are majority white.”

The shooting by Daron Wilson is being thought of by many as an unforgivable act of police brutality, but Gordon of his own has a theory about the reasoning behind it all.

“It is one of those very small towns, and they have trouble paying for basic services.

So to compensate they practice very aggressive policing,” Gordon said. “They’ve got officers walking from door to door saying, ‘There’s a crack in your sidewalk. I’m charging you $25. And if I come back tomorrow and see that it’s not fixed, I’m charging you $50.’”

The financial instability, as well as the divided population, create a more likely situation for incidents like the Michael Brown shooting to occur. The problem doesn’t appear to be improving.

“There’s also just the casual racism of white cops being suspicious of black kids, and vise versa. Part of it is the need to fine people, and another part of it is petty reasons just to raise money,” Gordon said. “Over time, this continues to create bad relations between citizens and the police.”

Gordon has some suggestions intended to lead Ferguson towards financial and social stability.

“If the background issue is the inability of the city of Ferguson to run itself, they need to share tax revenues across the area,” he said.

The varied incomes and resources within the city create a huge divide among the whole community. Gordon believes that this is the source of the problem.

“Schools are a basic public service that shouldn’t be determined by how much money people have,” Gordon said. “The community and the state should pay as needed rather than by who has money and who doesn’t. Otherwise poor schools get poorer! It’s the kids who really need it that are getting the worst education, and they can’t escape their neighborhood and life because they don’t have the resources to get out!”

Racial profiling and economic chaos can be a problem anywhere. Though it may have improved, its impacts are visible everywhere, even in Iowa City.

“I would not say it’s entirely a racial issue in Iowa City,” Gordon said. “However, certain neighborhoods get more attention from the police.”

Though less severe in Iowa City, elements of the Ferguson story can occur any time you have a minority in a contained part of town. Profiling is often unique to such areas and their neighborhoods.

“There’s a strong amount of profiling on my street. It’s over-policed and there seem to be constant patrols,” Gordon said. “There are the same sort of dynamics at work, the assumption that the local population is prone to breaking the law.”

In Our City

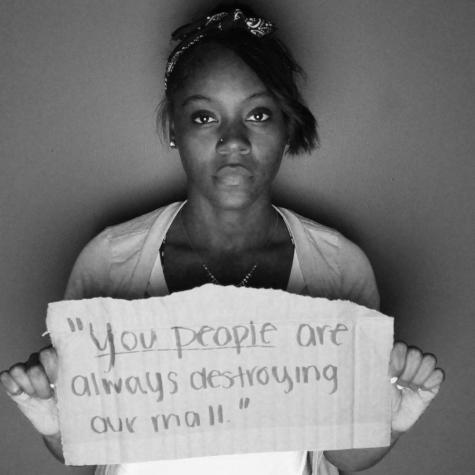

In response to the situation in Ferguson, a group of more than eighty people gathered at the Iowa City pedestrian mall on August 21st to protest racial profiling and the excessive force and militarization of local law enforcement.

“I definitely think racial profiling happens, but sometimes I think the claim of racial profiling can be exaggerated,” Logan Lafauce ‘15 said. “Something happens between an officer and a white person and there’s no problem, but the same will happen between an officer and a minority and all of a sudden it’s a problem.”

A traffic study analyzed earlier this year by the Iowa City Police Department showed that minority drivers were stopped and searched at a disproportionate rate in comparison to white and Asian motorists throughout the Iowa City area.

The study was conducted by St. Ambrose University professor Christopher Barnum, who analyzed six years of traffic stop information recorded prior to 2013. The results of Barnum’s study were presented to the City Council in June, but Iowa City Councilman Kingsley Botchway II requested further analysis due to Barnum’s claim that he didn’t have enough information to prove that the disproportionate traffic stops in Iowa City were a result of racial bias.

When the study was presented to the City Council, Police Chief Sam Hargadine the results were a concern, but he did not believe any of his officers had ill intent. Both he and Barnum stated the time period with the greatest amount of uneven traffic stops followed increased police activity because of concerns of violence in the area.

“We do participate in hot-spot policing,” Hargadine said in response to the study results. “If there’s a problem in town, we are expected to go in and take care of it.”

City High teacher Carrie Watson grew up in Iowa City, and being familiar with the police department, agrees that most officers are well-meaning.

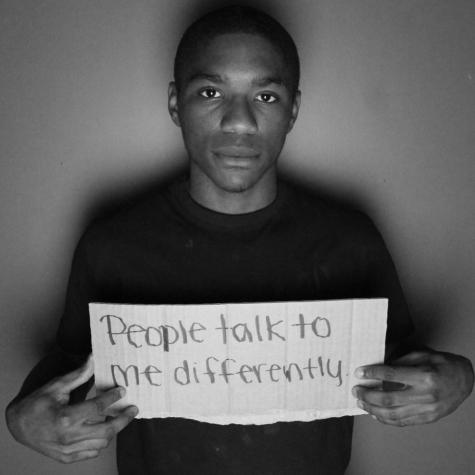

“I don’t think our police department is going out and saying we’re going to arrest every black man that we possibly can,” Watson said. “I think their goal is the same as everybody’s in that they want to create a community that is as safe as possible, but we do know as human beings through socialization there are stereotypes that are embedded in our society, and whether we are willing to admit they exist or not in our brain, they are entrenched in our subconscious and to claim that they’re not is ultimately never going to solve the problem.”

Shane Bracko ‘15 agrees with Watson about the evolution of stereotypes.

“I’ve had a few instances [with racial profiling],” Bracko said. “I come from Mississippi and I’ve seen it before. For some people it’s just a way of life because that’s what they were taught.”

Bracko also sees stereotyping as being the root of the profiling issue.

“Stereotypes work,” he said. “If someone is constantly labeled as being a certain way, they can easily become that stereotype. I feel like a lot of people become that stereotype because that’s what they are labeled as so often.”

Lafauce shares Bracko’s point of view.

“I think profiling is based off of the fact that there are stereotypes, which aren’t always fitting, but some stereotypes exist based off the actions of a certain group of people,” Lafauce said. “That doesn’t apply to every single person in that group though, which is the common misconception.”

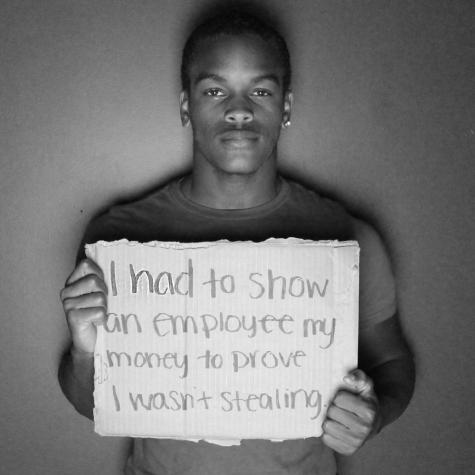

Sheldon Brown ‘16 has also had experiences with racial profiling.

“It’s about 8 o’clock, I’m walking past the light by the downtown area,” Brown said. “The police officer pulled up, flashed his light and told me to stop. He asked me to open my bag because there had been some stealings in the area.”

Brown felt that he was stopped unfairly by Iowa City Police.

“I was just walking, and I was stopped for no reason,” Brown said. “There were other people walking downtown, but he stopped me.”

As incidents of racial profiling gain more media attention, Watson hopes conversations about the issue will continue in our community.

“What we need is a honest discussion about racism from all sides with less finger-pointing and more collaboration,” she said.