Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

In the Middle: A Refugee’s Journey From Congo to Iowa

October 11, 2016

Aimée Nyamadorari ‘17 did not realize that she was in danger when the sound of a church hymn woke her up in the middle of the night.

The year was 2004. It was a warm August night, and Nyamadorari lay beside her parents, her five siblings, and her aunt in Gatumba, a Burundian refugee camp. At 10 o’clock, the alleluia of a familiar church melody began to echo among the tents, waking Nyamadorari from a restless sleep.

Nyamadorari tried to ignore the music and fall back asleep, for that night, she and the other refugees were oblivious to the threat in their presence. The prayers came not from a pastor or priest; rather, they were sung by the rebel soldiers of the Forces of National Liberation (FNL).

Shouting and chanting, the soldiers slowly began to advance toward the grounds of Gatumba, causing a stir throughout the camp. Seconds later, the sound of gunfire pierced the night air. A relentless torrent of bullets followed.

“I was so scared,” Nyamadorari said. “There were a lot of kids, and a lot of them ran away because it was so scary. I didn’t know what to do. I tried [to stay back] and keep sleeping.”

Nyamadorari called to her mother to wake her, but heard no answer. Her father, hearing her cries, confirmed her fear: her mother had been shot dead.

“I told my little siblings not to cry, because the enemies could maybe hear them, and maybe even come kill me,” Nyamadorari said.

Upon hearing the gunshots, Nyamadorari’s aunt hurried over to their tent to pick up Nyamadorari and her younger sister, Sarah. However, Nyamadorari’s father was unable to flee, as he had suffered a bullet to the leg. Nyamadorari recalls feeling torn about having to leave her father behind.

“I didn’t want to leave my dad,” Nyamadorari said. “I said I wanted to stay with my dad. He told me to go, and said that he would be with me again soon.”

So Nyamadorari and her Aunt, with her infant sister in tow, fled the camp. Behind them, Gatumba had turned into a massacre scene. The tents had been deserted. Belongings were destroyed. More than a hundred refugees lay dead, including Nyamadorari’s mother and four of her siblings. As Nyamadorari escaped, she heard her father shout to God for forgiveness, to make peace before his death.

“They say, at that time, you had to ask God for forgiveness so you could die [in peace],” Nyamadorari said. “My dad started praying, saying ‘forgive me, forgive my family and my wife.’”

Born in Congo but raised in Burundi, Nyamadorari and her family belonged to the Banyamulenge ethnic group, and grew up in a decade surrounded by political and ethnic tensions. Congo’s recent conflicts date back to the 1990s and stem from the Rwandan genocide. The power struggle between political groups made it difficult for rebel forces to emerge as a cohesive governmental body. One such group includes the RCD-Goma, a rebel movement that has historically advocated for the Banyamulenge people. The RCD-Goma also share an intimate relationship with the Rwandan government, a fact that renders hostility among other Congolese ethnic groups against the Banyamulenge. This hostility was further provoked by the occurrence of a series of Congolese-Rwandan wars, ultimately putting the loyalties of the Banyamulenge people into question.

“They call us Congolese, but others call us Rwandans…we were just in the middle,” Nyamadorari said.

Burundi continues to live in the aftermath of the Burundian Civil War, which lasted from 1993 to 2006. Political groups, such as The Forces for the Defense of Democracy (FDD), clashed with the FNL over the division of power. Ethnic strife between the Hutu and Tutsi groups, which was thought to have originated from class conflicts, threatened political progress as well. The mainly Hutu FNL and the largely Tutsi FDD remain opponents to this day. Because the Banyamulenge were closely associated with the Tutsi FDD, they became a primary target for the Hutu FNL, much like Nyamadorari’s family’s experience in Gatumba.

Nyamadorari, her aunt, and her sister began to head toward a forest, where they happened upon a house to stay the night in. In the morning, Nyamadorari received a message from one of the men staying at the house: it was from her father, requesting to speak with her. When Nyamadorari was unable to make the journey back to her father, her aunt went instead. Her aunt returned later in the day, however, to deliver troubling news: her father had passed away.

“When my aunt came back from the visit crying, I knew [something bad had happened],” Nyamadorari said. “I knew then that my dad had died.”

Her father’s last words, as told by her aunt, still linger in her mind.

“He said that I had to be strong no matter what, and that I had to take good care of my sister. He told [my auntie] to take care of us two girls, because we didn’t have a mom and dad anymore,” Nyamadorari said.

Several hours later, a man arrived with a truck, offering to take injured survivors of the attack to the hospital. In the light of the day, Nyamadorari saw that her sister was covered in blood, and that she herself had been shot.

“I didn’t realize it at first,” Nyamadorari said. “I thought that I was fine, but my auntie said ‘no, they shot us,’ but I [insisted], ‘no, I’m fine.’”

The man from the truck bandaged her head, and took Nyamadorari and her family to the hospital. After their week-long stay, Nyamadorari’s grandmother arrived, requesting to see the bodies of her family members.

After the massacre, the FNL had set fire to the camp. Her mother’s body, only recognizable by the clothes that she wore, was still in the charred remains of her family’s tent.

“[My grandma] didn’t want to leave her daughter,” Nyamadorari said. “People came and tried to pull her away.”

As is traditional in Congo, children are expected to stay with the father’s family in the absence of the parents; however, due to her poor health and young age, Nyamadorari’s sister was sent to an orphanage in Burundi. Nyamadorari, separated from her younger sister, was sent back to Congo to live with her father’s parents. Two years later, Nyamadorari traveled back to Burundi, reuniting with her sister and residing in the orphanage. She and her sister lived there for ten years, alongside 62 other children who had lost their parents in Gatumba on that night in August.

Separated from the rest of her family, Nyamadorari sought refuge in the religious community at the orphanage.

“It was really hard [to look for hope]. The thing that helped me while living in the orphanage was our pastor,” Nyamadorari said. “He gave us courage through the word of God. I believed that there was no other man I could have trusted more, because I didn’t have my dad and my mom.”

Nyamadorari’s faith also gave her a greater sense of purpose and the strength to continue living.

“I told myself that I could trust God,” she said. “Because [the FNL] shot me, I was supposed to die, but God had a good plan for me.”

Nyamadorari also found solace in fostering relationships with the members of the orphanage – especially with the caretaker of the orphanage, who had a daughter of her own. Over a period of eleven years, Nyamadorari and her caretaker developed a close relationship. Today, Nyamadorari and her sister see their caretaker as a mother figure.

“To this day, we call [her] ‘mom,’” she said.

Although Nyamadorari was able to find comfort in the midst of her hardship, the tragedy still remained fresh in her mind. To cope, she tried to mask her emotions, but this still proved to be a challenge.

“Sometimes I would go through a bad time and I would go to my room alone. It’s just how I am; I don’t want to show others my pain. I tried to act like I was fine,” Nyamadorari said. “But when I was alone in my room, I still felt so bad.”

In her most difficult moments, Nyamadorari sometimes found herself doubting her desire to stay optimistic. In the subsequent years following the Gatumba massacre, however, Nyamadorari was able to turn the tragedy of her family’s death into a more motivational sentiment—a daily reminder of why she had to keep living and fighting for hope.

“I sometimes ask myself why I [fought to stay hopeful]. I told myself that it was because I had a father and family,” Nyamadorari said. “The other thing that helped me to move on was remembering all my brothers and sisters who had died. Back when my mom was pregnant [with one of my sisters], she told me that she wanted to have a girl, because all the other girls were dying, and she didn’t know why. In that moment I asked myself why I was still alive. It was just the grace of God. That kept me going.”

For ten years, Nyamadorari and the other children in the orphanage awaited American Visas. For them, the Visa represented their chance at a better life.

“When the lady at the orphanage told me I was [getting my Visa], [saying that the] government wanted to take us kids to live in the United States and have a good life like the others, I was like ‘wow, that’s good!’ I was so excited I started crying,” Nyamadorari said.

In 2013, Nyamadorari, her younger sister, her aunt, and their caretaker moved to the United States to begin their new life. They initially arrived in Illinois, but due to the lack of suitable employment opportunities, decided to look at other options. A phone call from Nyamadorari’s cousin informed her family about job openings in Iowa, to where they relocated soon after. Nyamadorari’s aunt found a job in Iowa City, and their caretaker landed a job in Cedar Rapids.

———————–

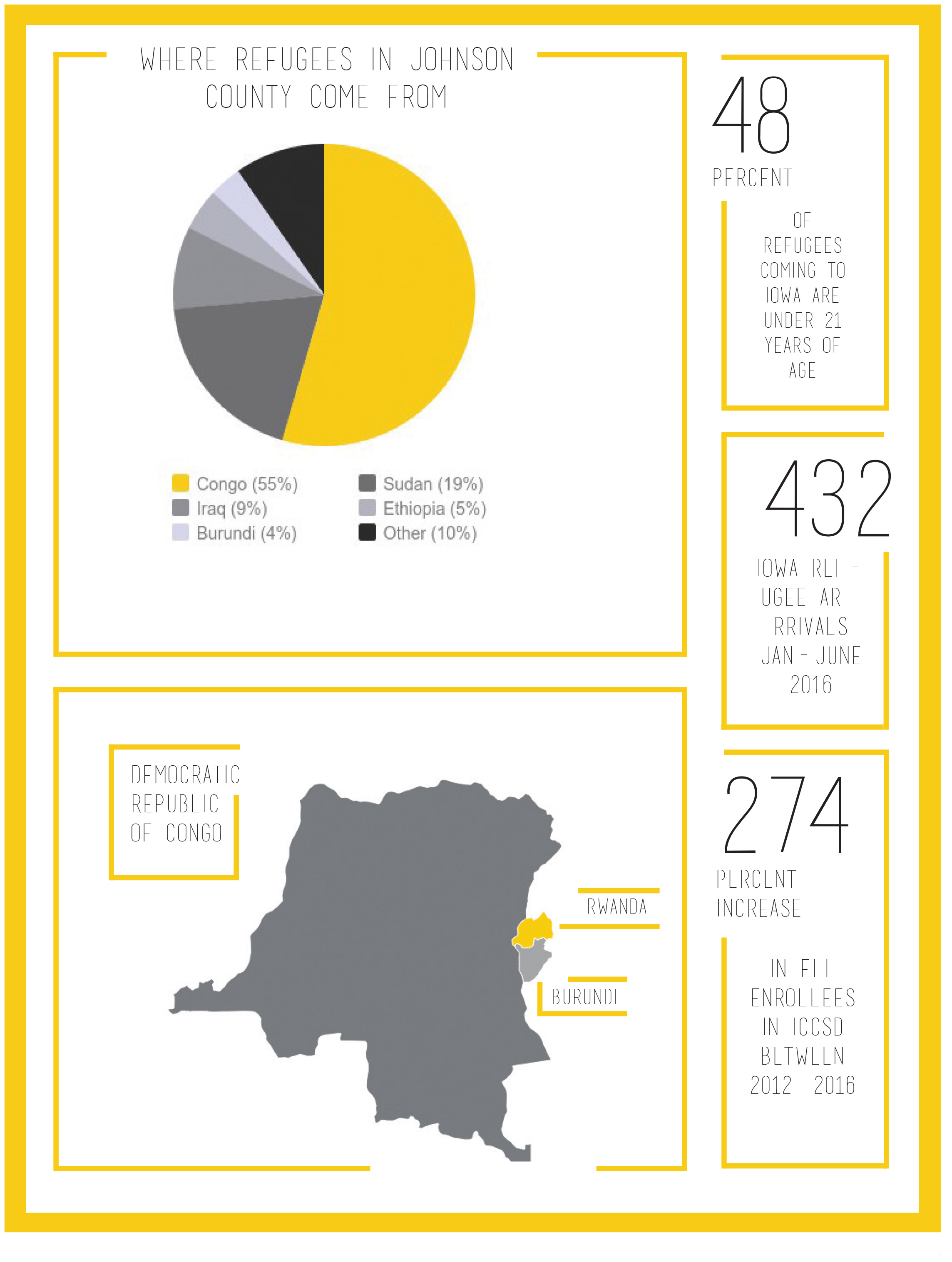

In the past decade, an increasing number of refugees like Nyamadorari have been arriving in Iowa to escape from violence, political instability, and lack of access to education in their home countries. In Johnson County, over half of the refugees settling in the area have come from Congo or Burundi. Because of this influx, the Iowa City Community School District’s ELL program has grown by 274% in the last five years.

Izaskun Lejarcegui, a paraeducator and ELL tutor, feels that the ELL program was unprepared to help the influx of refugees.

“In many ways, we are not prepared,” she said. “[The refugees] come in waves, and sometimes I don’t think authorities realize just how many are coming.”

Lejarcegui, who also interprets for a Children’s Clinic, the judicial system, and the Department of Human Services, started working with Congolese refugees at Alexander Elementary School, where the recent arrival of a group of refugees called for the assistance of an interpreter. In her experience, many refugees come to Iowa seeking better educational opportunities.

“They leave [their home countries] to give their children a chance to have an education. They see these big buildings, like the new Alexander Elementary, and they are shocked by the opportunities and resources of our schools,” Lejarcegui said. “We have everything, whereas they often come from places where there is only one teacher in a classroom of dozens of kids of all ages, without books, pencils, or paper.”

Their desire for better educational opportunities, however, is often impeded by language barriers at school. Although a portion of the Congolese refugee population has some experience in the English language, the majority speak French or Swahili. Since very few teachers speak foreign languages with a degree of fluency, this can make it difficult for them to connect with ELL students and help them feel that they belong. Furthermore, the refugee and immigrant students are often placed in courses in accordance with graduation policies; however, many of these courses are far beyond their English ability, which further frustrates and alienates them.

“When I interpret for parents, I can feel the profound anxiety they have about their children’s struggles at school. Worse, the parents often speak even less English than their children, work night shifts, and face other challenges that make it impossible for them to communicate with the schools or help with homework,” Lejarcegui said. “Sadly, I do not have enough hours in a day to help them all, and the district does not have the resources to hire more people with the necessary languages, specialized skills, and experience to attend to this need.”

Outside of school, language barriers force refugees to face additional obstacles in securing employment, education, and adequate housing. Iowa’s exponential growth in the immigrant population has exacerbated the shortage of affordable housing. The surge in demand has caused home assistance waiting lists to grow beyond capacity. The situation is worsened by the large number of children in the families.

“Housing has become one of the main problems for families,” Lejarcegui said. “Sometimes [I will see] three or four families living together in the same apartment, sharing two rooms.”

Another pressing issue is poverty. In some cases, families lack sufficient food and other bare necessities in their homes. Lejarcegui, who works closely with these families, notes that it can be shocking to see it firsthand.

“There is a lot of poverty; I see this poverty when I visit immigrant and refugee homes. Their homes lack beds, tables, sometimes chairs, blankets, rugs, towels…basic necessities. I think that most of the Iowa community population is unaware of the poverty that we have right here in our own city, especially the school children, who might not know about the poverty among their classmates,” she said.

Lejarcegui and other teachers in the ELL program try to alleviate some of these problems, at least while refugee students are at school, but their power to help them is constrained by a lack of adequate funding and resources. Lejarcegui stresses that the needs for multilingual services is urgent.

“Refugees and other immigrants need services in their own languages,” she said.

Lejarcegui also advocates for greater connections between the school and its ELL students.

“In classes, students should be more aware of each other. It is surprising to me to talk to City High students who are only barely aware that we have students from different countries who speak different languages sharing their classrooms. At City High we should find ways for all students to interact with each other—not only on the athletic fields, but through music, shows, clubs, games, parties,” she said. “Our ELL students are great people, and increased interaction would be beneficial for all.”

Despite the challenges her job entails, Lejarcegui finds her work extremely fulfilling.

“It brings me happiness,” Lejarcegui said. “A day doesn’t go by without students saying ‘thank you.’ It’s super rewarding.”

Helping others, Lejarcegui believes, should not only happen within the settings of a school; she consciously makes an effort every day to give back to her community.

“What I try to pass on to my children is that as you [live your everyday life], you need to make the time to make a difference,” Lejarcegui said. “To live a life that touches others is amazing beyond compare.”

————————

In 2013, Nyamadorari started school at City High. Although she had learned some English in school in Burundi, her inability to speak the language made her feel isolated at school.

“When I first came to the United States, I could understand some things, but [social situations] were still really hard,” she said. “I remember the first day that I came to City High, I was so worried. I couldn’t answer the teacher in class.”

Although some other students spoke Swahili, Nyamadorari felt that even interactions with her peers were fraught.

“It was very hard to make friends. Even now, I am sometimes scared to talk, because I am not comfortable,” Nyamadorari said. “Here the kids speak the same language, but we are still different. I am worried that I might say something that will make someone upset.”

To help integrate her into the City High environment, Nyamadorari was enrolled in the ELL program. Maria Velina McTaggart, ELL teacher, has been one of her biggest mentors. In addition to teaching English as a second language, McTaggart hopes to instill a sense of confidence in her students.

“I tell them that there are so many opportunities for them once they leave City High, and that if I can make it, then [they] can make it as well,” McTaggart said. “I know where they’re coming from, and I just relate to their personal experiences. I want to see them succeed, and get good careers and make something out of their life.”

Outside of the classroom setting, McTaggart also hopes to guide her students by being an adviser and close confidante.

“I just make them feel welcome. I just let them know that if they ever need anybody to speak to, that I’m here for them, and I might not offer them any advice, but I’m a person who can just listen to them,” McTaggart said.

Nyamadorari’s new life also comes with new responsibilities. In order to help support her family, she and her aunt have to work long hours.

“My auntie worked late at night and [also] had to go to school to be able to support [my sister and me]. In my junior year, I had to work to to help the family out,” she said.

For Nyamadorari, growing up has also meant having to answer difficult questions from her sister.

“Now my sister wants to know what happened. She asks about our parents, but I don’t like to talk to her about it,” she said. “I act like I don’t know anything, because I was young at the time too. People always tell my sister that she looks like her dad and mom, and she wants to know how they really were.”

While it’s difficult for her to talk about her parents with her sister, Nyamadorari likes to stay connected to the memory of her family and her heritage through singing in church.

“People who knew my family said my mother was a singer, so I know where I come from,” she said.

Singing also helped Nyamadorari feel less isolated as she was learning to speak English.

“I love to sing and I want to share it with others,” she said. “When I’m singing, I feel like I’m different, even if I don’t understand the language I sing in.”

With the help of teachers and mentors, Nyamadori’s English improved; school became more manageable, and she was able to make friends.

“Life in Congo was hard, really hard,” she said. “But I can tell that life here is becoming easier. Although sometimes I don’t get off work until ten o’clock and I still have to finish homework, I can really notice the differences in my life.”

After graduation, Nyamadorari intends to continue her education, and stay close to her family in Iowa.

“I think my auntie wants to stay in Iowa. She loves Iowa and her work,” Nyamadorari said. “I couldn’t imagine moving to another state; my mind is here in Iowa.”