A Bitter Pill to Swallow

Since 1999, prescription opioid sales have nearly quadrupled, as have opioid and prescription drug overdose deaths. Prescription drug abuse, especially of opioids, is sweeping the nation, and Iowa is no exception.

February 8, 2017

Imagine an opioid user. Do you have a clear picture in your head?

Now, meet Abe*. He’s an honors student, and an athlete. He is white, his parents are affluent. Abe also regularly uses prescription drugs.

For several years, he’s smoked marijuana routinely, but more recently, he was introduced to lean, a drink that mixes soda with prescription cough syrup that contains codeine or other opiates. From there, he also began to experiment with prescription opioids like oxycodone as well as prescribed stimulants like Xanax or Adderall.

“I love [oxies],” Abe said. “It was probably a couple months ago that I first did it. I’m not going to lie, it doesn’t come around that often, but if I get my hands on it, I’ll definitely get it, because it’s like the lean, it’s just even better.”

When it comes to using—especially for the first time—Abe is calculated: he makes sure that he has nothing going on later that day; he researches dosages beforehand; and he prefers to be in a controlled environment—with a few close friends or by himself, rather than at a party.

“My main principle is that I get my stuff done during the day—I don’t need drugs for that at school—and then at the end of the day when I have free time, that’s when I like to do the other stuff, the oxy or whatever, if I have it,” Abe said.

After all, he says, he doesn’t want his high school legacy to be that of what he calls a “druggie” which he defines as someone who delves into a myriad of drugs, and who will stop at nothing to get them. Rather, he characterizes himself as unassuming, his drug use “a low-key thing,” and his tendencies controllable.

“I’m not going to say that I’m probably slightly a druggie, if you use [my] definition,” Abe said.“But I really like to not think of myself as that, because I’m not an addict and shit. I have a good time but I can still handle my shit. [I’m not] the type of druggie that will do anything for drugs. I’m able to control it, but I still do drugs.”

While Abe enjoys using prescription opioids like oxycodone, he is careful to avoid other stronger opiates such as heroin. With heroin, he fears, the threat of overdose and addiction looms greater. Indeed, heroin-related overdose deaths have tripled in the past decade, and heroin addiction has doubled, according to the CDC.

“It’d be awesome [to do heroin]; it’s the best one… that’s what it’s all hyped up to be, it’s the top thing,” he said. “But I would never go down that route.”

To avoid dependence, Abe tries to space out his usage. Sometimes his spacing is unavoidable as his access to prescription drugs is spotty; people who deal him marijuana often avoid prescription medications, he says. Instead, they usually come from friends with prescriptions or from a vast, tenuous network of people who know people with access to painkillers or anxiety medications.

Abe feels that these connections are sometimes ethically dubious. Once, for instance, he got prescription opiates “through a friend, through another friend,” who he knew somewhat. That last friend, the source, had access to opiates because his mother was dying of cancer.

“You get them from whoever you can get them from, anyone. It could be the kid with ADHD, it could be somebody that knows somebody that has cancer and has these crazy painkillers or something,” he said. “But it’s kind of messed up in that way if you’re looking for them and getting them from those kind of people. It’s a shady thing.”

Increasingly, Abe is a typical opioid user. The stereotypical image of a young, black, inner-city dwelling male heroin user, fueled by media portrayals and our collective imagination, is in fact, largely a relic of the 1960s. Indeed, according a 2014 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in the 60s, 82.8 percent of opioid users were male, 60 percent were nonwhite, and their mean age was 16.5. In the past several decades, however, the demographics of opioid users have shifted to an older, whiter and more affluent audience. According to that same study, 90.3 percent of opioid users are white, men and women use at about equal rates, and their average age has increased to 22.9. Where opioid usage was once concentrated on the coasts, it has now spread to middle America. The spread, according to the CDC, has been correlated with an increase in prescriptions for painkillers. Between 1999 and 2014, the number of prescriptions written for oxycodone and hydrocodone, two types of opioid painkillers, have increased from 76 million to 207 million, making the United States one of the largest consumers of these painkillers in the world. Largely, like Abe, they don’t initiate opioid use through heroin; rather, the overwhelming majority get their drugs from friends or relatives for free or from their own prescription, according to the National Survey on Drug use and Health.

Abe is, however, somewhat atypical in his usage patterns; often, users start with prescription drugs, become addicted, and move on to heroin because it’s cheaper and gives a more powerful high. Both prescription painkillers and heroin, contrary to Abe’s belief, carry high risk of overdose and addiction. Especially if snorted or injected, both drugs can be very potent and put users at risk of contracting diseases such as Hepatitis C or HIV. With the increased prevalence of such drugs in the past few decades has come a rise in overdose deaths; between 2000 and last year, the number of opioid overdose deaths tripled.

While Abe has never worried about overdosing, the possibility remains a reality for many prescription drug users. Meet George*. He, like Abe, is a thoughtful person, a good student, and a drug user, but from there, their stories diverge.

George was introduced to prescription drugs his freshman year. He had a acquaintance who he characterized as “emotionally unstable” and unable to make friends. The way that he tried to connect with George was by supplying him with prescription drugs like hydrocodone and oxycodone painkillers and Xanax, an anxiety medication.

“it was a really false sense of a friendship,” George said. “Basically he would just come into class and give me a bottle of pills and say, ‘take whatever you want and give me the rest.’”

George had started using drugs on a regular basis a few years prior. Mostly, he used marijuana and dabbled in psychedelics. When he was first introduced to prescription drugs, George was smoking every day, which worried his mom, who herself had struggled with drug addiction in the past. His mom, concerned with his usage, started testing him for THC (a compound in marijuana). To avoid upsetting her, George started using prescription drugs on a daily basis instead.

Unlike Abe, George was not calculated when he experimented with new prescription drugs. Instead, he would take them in random quantities and combinations.

“I really had no idea what I was doing,” he said. “I would do this thing where I’d take one, wait ten minutes, but I thought that it had been thirty minutes, and I didn’t feel anything, so then I’d take another one, and then to make sure that the high was really good, I’d take another one, then another one. I would think that it wasn’t really working, but then it would just hit me all at once. When you did that many, it wasn’t a steady ascension but it would just hit me.”

From there, he said, he would often experience muscle spasms and his jaw would tense up. But the descent from the high was worse—as the drug wore off, George would find himself feeling uncomfortable and prickly.

“I’d be sweating and irritable, so a pencil tapping would sound to me like a bomb going off,” he said. “Everything was amplified to the most negative degree, and everything just made me want to go off on anything or anybody.”

A few times, George overdosed, which he defined as losing consciousness and control of his body.

“Whenever I was on it, it was never scary to me,” he said. “There was always a short period of time before the overdose hit, it was the best feeling that I had ever felt.”

For the most part, George didn’t worry about his drug use when he was on drugs, unless he was at school, where he worried about getting found out or accidentally overdosing. One morning he was at school, but, realizing that he had used too much, decided that he had to leave. He left through the back door, but soon he found himself unable to walk, so he started to crawl in efforts to get out of sight of the school. He managed to crawl behind a temporary. When he woke up, it was dark outside.

“I’m just so thankful that [I didn’t lose consciousness during the] winter, because I probably would have been seriously injured,” he said. “Even as it was, I was in pretty bad shape. I had to call one of my friends to pick me up, because I couldn’t really walk.”

Sometimes when he overdosed, George would go to the hospital; other times, his friends would pump his stomach.

Soon, George got to the point where he was using so frequently that taking prescription drugs became a daily motion.

“I was just doing it to sustain natural living,” I said. “I had such a high tolerance by then, that when I was on the drug, even if I didn’t feel the euphoric feelings, there was a baseline normality in it. Or I would try to get really high, and I’d go past the threshold and it would just be a terrible time.”

After several months of using prescription drugs daily, George started feeling some of the physical side-effects of his use. He was losing a lot of weight—the drugs he was taking made him lose his appetite—and he was tiring of how using made him feel.

“Of course, if it’s prescribed, that’s fine, but if you’re taking way too much for your body to handle every day, it becomes too much,” he said. “I started having my muscles lock up, and I just felt like a hollow person—like I had no organs or bones. I was struggling to move and talk and think. Everything was just completely deteriorating. My mom would talk to me, and I’d just be in this haze, and it would be like I was in another world.”

Beyond his physical health, George realized that his relationships had suffered during his period of heavy use.

“I didn’t want a close relationship with anyone, didn’t care about it at all,” he said of his friendships. “My drugs were basically my intimate partner—a really unhealthy relationship. I neglected all of my positive friendships, and I completely submerged myself in negative relationships.”

After about a year, George stopped using prescription drugs. He says that he didn’t really feel the effects of withdrawal, he thinks because he continued to use marijuana and psychedelics regularly afterwards.

A year later, he and his family decided that he should try treatment for his drug addiction.

“I think that [my mom] thought that she could handle it, but eventually she just realized that she couldn’t do it, and that I had to go to treatment,” George said. “But that was way after my very heavy pill usage, so I really could have used treatment more when I was using more heavily, around ninth grade, but it just didn’t happen. My mom thought that it had to be just last resort, but eventually she realized that I had to go to treatment.”

His treatment experience, however, didn’t prove to be particularly helpful. George found that the staff had little experience with addiction and that the other young people there were unengaged.

“The only thing that [treatment] really did for me was that it gave me a controlled environment, so I was able to read, which really helped me. But as far as staff, treatment was not a good experience at all,” he said. But, he conceded that treatment did provide him with some perspective. “Even now when I use drugs, I can see through my bullshit, where before when I used drugs, I created that bullshit but I couldn’t see that it was actually false.”

When he got back from treatment, George also realized how much his drug usage had colored his classmates’ perception of him. For instance, George’s English class was reading The Great Gatsby, and during one of the discussions, he made an insightful comment about the book. George looked around the room and saw that his classmates’ jaws had dropped.

“Just by their surprise that I was saying those things, I realized that basically these years of high school were just jokes; no one took me seriously and everyone just thought that I was a stupid stoner,” George said. “People discredit everything you say, that’s probably the worst thing about my drug use, is that when people know, they don’t take anything that you say seriously.”

George still considers himself to be an addict—he goes back and forth between staying clean, and relapsing into using in marijuana and other drugs (though avoids prescription drugs now). He wants to get away from drugs permanently, but struggles with it immensely, as his roommate deals marijuana and he still finds himself craving them.

“It felt like [Sisyphus] any time that I was using drugs consistently, like I’m just constantly pushing the boulder up the hill, only to have it roll down each time,” George said. “I know that there are people who struggle with [addiction] through their whole lives, but I just feel like one day… I’ll want to stop using, and then I’ll stop. Like I just feel like that’s going to happen, and it feels so real, but I know that that’s never going to happen if I’m still on the search to use drugs.”

Although he hasn’t returned to using prescription drugs, George sometimes worries that he will return to using them. He’s getting his wisdom teeth removed soon, which means that he will likely be prescribed painkillers.

“It makes me pretty nervous,” he said of the painkillers. “I know that I’m going to ask my mom to keep them for me, but it’s kind of scary going back to that realm.”

A

ccording to a 2014 CDC study, about 55 percent of people who had used opioids in the preceding year had gotten free prescription drugs from a friend or relative. Another senior, Dixie*, is one such drug distributor.

Dixie was diagnosed with ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in the third grade, and has been prescribed the stimulant vyvanse, a drug similar to adderall, since. Her diagnoses and subsequent prescription is not at all unusual: in fact, both the percent of diagnoses of ADHD and prevalence of ADHD medication has increased steadily in the past decade. Dixie had taken her prescription routinely up until her sophomore year, when she began to experience its adverse effects.

“I had very positive experiences with [vyvanse] in elementary school but as I got older it started numbing my personality a little. My friends at school would be like ‘are you sad?’,” she said.

Vyvanse, while allowing Dixie to work diligently and retain focus, also put her in what she describes as a “zombie-like” state, where she felt numb and not like herself. It was then, during her sophomore year, that she began taking vyvanse with less routine.

“I was never really consistent on taking my medication,” Dixie said. “So I would always have leftover, and I would just tell my mom like ‘I’m out [of medication], get more.’ And she never questioned it.”

Upon partially stopping medication, Dixie’s grades dropped a bit (but not enough, she says, to justify taking it fully again, only to experience its numbing effects), and she was left with a hot commodity: a mostly untouched bottle of pills.

Dixie’s close friends, who knew of her medication, began asking her for it.

“They reached out to me. They were like ‘I know you’re taking [vyvanse].’ It was almost a situation where I couldn’t say no, but I also wasn’t saying no—I could’ve. It just wasn’t a big deal to me,” she said.

For a six month period at the end of her sophomore year and beginning of her junior year of high school, Dixie began dealing on a small-scale, only to close friends. However, she is hesitant to label her behavior as that of a drug dealer; rather, she describes it as more of a favor to her friends.

“For me, a dealer deals to a ton of people, and you have to have prices for different things, and they do it for the money,” Dixie said. “I wasn’t doing it for the money; it wasn’t about that.”

She would share her prescription either as reimbursement for previously shared marijuana or for the small price of five dollars per pill. She shared her prescription with four different people over the sixth month period (three that she knows of, and a one person deviation because “there’s probably someone else.”). Because her dealing was spurred from friendship, Dixie was careful in the amount she would give to each friend, and which friend she chose to give it to.

“They asked me for it more frequently, but towards the end of it, I got sketched out and I was like, I don’t really feel like I want to do that anymore,” Dixie said. “I’m not like this, I’m not a dealer, these are just close friends that I gave to once in awhile.”

Dixie’s sharing in itself often happened right outside her house. Her friends would come to pick the prescription up, and she would walk past her family in the living room to the front door to deliver the pills. When her dad questioned her behavior, she scrambled with excuses, often saying that she needed fresh air.

“I was always nervous, it was like always something bad that I was doing, but I was doing it anyway,” she said.

Dixie also worried about the unfair advantage she was giving her friends, as their primary motive in using vyvanse was to take or study for college entrance exams, such as the ACT.

“It kind of messes me up when people are taking it for the ACT,” Dixie said. “Because there are people who don’t have ADHD and are not taking the medication and there are people who are, so they are going to get better scores.”

While vyvanse does not alter intelligence, it increases focus for users without ADHD. Dixie had reservations about facilitating her friends’ behaviors, she is inclined to think that they would’ve found an alternative, and perhaps less reliable, source for them.

“I do think that [if I hadn’t dealt to them] they might have even found a more dangerous way [to access vyvanse],” Dixie said.

Ultimately, Dixie stopped being prescribed vyvanse altogether, as she prefers how she feels when she doesn’t take medication, and she no longer deals to her close friends. Looking back, Dixie isn’t regretful of her dealing, but is concerned about the highly addictive nature of the drugs she shared; in fact, prescription stimulants have become the second most popular illicit drug, only second to marijuana.

“[Stimulants] never should be a crutch, and I don’t want to be the person that gave them that crutch,” Dixie said.

A

fter working in Washington D.C. for several years, Sarah Ziegenhorn ‘07 returned to Iowa City for medical school in 2015. In D.C., she had been working at a think tank called the Institute of Medicine by day, and at night, she would volunteer for a non-profit harm reduction organization. According to the national Harm Reduction Coalition’s website, the goal of harm reduction is to “meet drug users where they’re at,” in order to address needs and safety of communities and individuals. There isn’t, however, a universal formula for implementing harm reduction. HIPS, the organization that Ziegenhorn worked with focused specifically on helping those impacted by sexual exchange and/or drug use. The program provided mobile outreach services for sex workers and drug users, which meant that they traveled around the city and provided materials for safe use and helped them treat wounds. The organization would also help connect people with social work, health care, and addiction treatment services if they wished.

When Ziegenhorn returned to Iowa, she sought out a similar harm reduction group because she enjoyed the community, both of fellow volunteers and of people that they helped. However, she discovered that there were no harm reduction groups working in Iowa at the time.

Because of the dearth of organizations, Ziegenhorn thought that there might not be a large community of injecting drug users. Later, as she was doing research about women who used drugs during pregnancy, Ziegenhorn learned that that was not the case.

“As I started learning more about substance abuse in Iowa, I realized that there actually was a lot going on but it’s kind of like a lot of social justice issues in Iowa—it’s not really communicated through the news, it’s not well talked about and it doesn’t draw as much attention as similar issues do on the coast,” she said.

From there, Ziegenhorn and her classmate, Cameron Foreman ‘07, decided to host a conference for other medical students to educate them about harm reduction.

“We decided to have this conference at our medical school about opioids in Iowa just to talk about the issue, just because it hadn’t gotten very much attention from the medical community other than people are talking about how to describe fewer pain medications and how to get fewer drug seekers in their clinics,” Ziegenhorn said. “A lot of the government response was coming from the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Department of Justice and Police, and their job is not to deal with public health, their job is to prosecute people. So we did this conference to educate medical students about harm reduction and we did, and then we decided that we might as well just start to do harm reduction outreach here in Iowa.”

The Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition became an official nonprofit in October 2016. Currently, they do outreach in Iowa City, providing kits for safer drug use and operating a hotline. For Ziegenhorn, harm reduction work is an equalizer—a way for her to talk to and learn from drug users without an imbalance of medical-student-community member power.

“I like connecting with people, especially on a level where I’m not coming in as a professional provider in a white coat who has a ton of medical knowledge and power,” she said. “I like to be able to meet people where they are, as a person who lives in the same community as they do.”

Beyond the work that her organization does, Ziegenhorn also hopes that more legislative efforts will be made to help current opioid users.

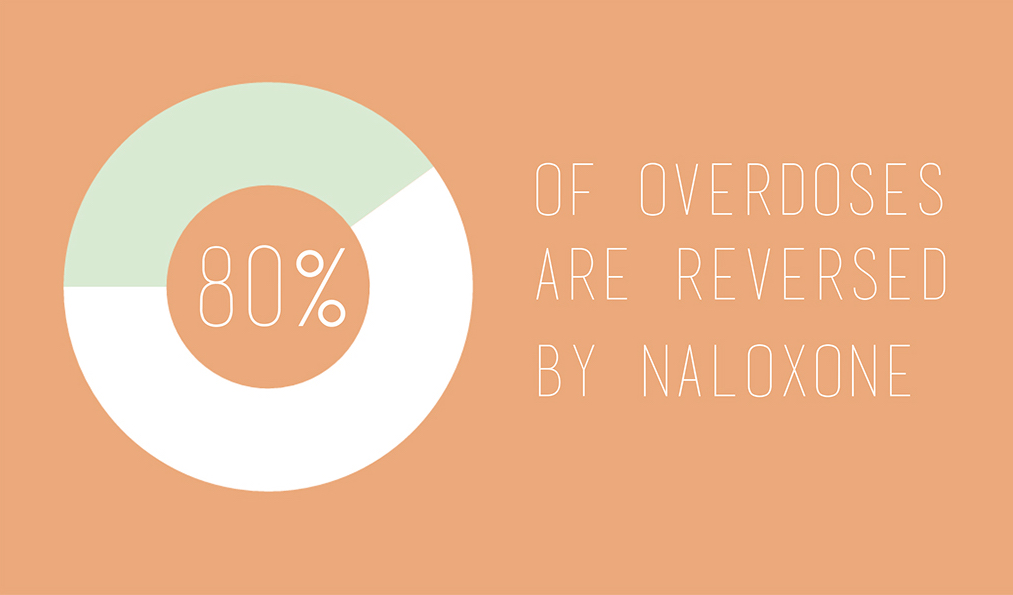

One way of reducing deaths from overdose is through administration of naloxone, a drug that can counter opioids and temporarily prevent an overdose death in most cases. The Iowa legislature has recently made it legal for pharmacies to provide naloxone to people without prescriptions, but Ziegenhorn thinks that access needs to be expanded further yet.

First, she fears that users won’t know to go to pharmacies, and second, many pharmacies in Iowa still don’t carry the drug. When we reached out to Iowa City area pharmacies, this was largely the case. Of the four that we talked to, two pharmacies were looking into getting naloxone, but just one had it in stock.

According to a 2015 study, nearly 83 percent of overdoses are reversed by other drug users, and of those reversals, 80 percent received the naloxone from a harm reduction organization. Given such statistics, Ziegenhorn hopes that the Iowa legislature will expand access to and distribution of the overdose reversal drug.

The Clinton foundation has also taken part in harm reduction efforts, offering naloxone for free for every high school in the United States to have on stock. The ICCSD, however, currently does not have naloxone on hand; City High School Nurse Jen BarbouRoske cites the fact that there is not always licensed registered nurse in the building at all times as the motive behind City High’s not carrying naloxone.

Another aspect of Iowa law that Ziegenhorn takes issue with is the lack of a “good samaritan law,” that would protect drug users who call 911 in the event of an overdose. In Iowa, the law only protects people from prosecution if they attempt to reverse an overdose that goes wrong. Even in states with laws that protect people from getting charged for possession when they call emergency services in an overdose, Ziegenhorn says that law enforcement can find loopholes and charge them with disorderly conduct or disturbance of the peace.

Ziegenhorn’s organization is also actively advocating for a law that would legalize needle exchange programs in Iowa. Under the new bill, which is due to be introduced in the 2017 spring legislative session, users would be allowed to carry needles if they were participating in needle exchange programs. With these new rules in place, Ziegenhorn plans to use her organization to bring better Hepatitis C and HIV prevention, as well as a sense of security to Iowa drug users. Currently, the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition provides kits with “cottons” and “cookers,” which allow people to inject drugs safely and sanitarily, but they still fear that carrying such materials could lead to prosecution.

“People in the community don’t know what counts as paraphernalia and whether it will get them arrested or not,” she said. “People are especially worried that if they’re carrying around cottons and cookers and they’re stopped by the police that they’ll get arrested, which is not legal, but they are definitely fearful, and they have good reason to be.”

Indeed, a 2016 ACLU report states that Iowa is the number two state for most racial and class bias in drug related arrests. Despite the consistent CDC national data suggesting that people use drugs at the same rate across all ages, income groups, levels of education and ethnicities, drug related arrests in Iowa are disproportionately people of color.

Ziegenhorn also sees room for improvement in addiction treatment services offered in Iowa.

“I think that one issue is that people think that you have to not use drugs at all, to be healthy you have to have no drug use, but that doesn’t always work for everyone,” she said. “People just need support…To put that more simply, people that have a harm reduction support service that they engage in are more likely to stop using drugs and stay off of them long term.”

Overall, however, Ziegenhorn has been impressed by the federal public health response to the national opioid abuse crisis.

“A lot of people that i know that have been working in the harm reduction world since the 80 are really used to their work being seen as evil or enabling and really getting trashed a lot for what they’re doing, they’ve been, and I’ve also been, excited to see that the Obama administration has been really supportive of harm reduction work.”

Nevertheless, she anticipates that much of the federal support for harm reduction organizations will diminish during the next presidential administration; much of their work hinges on a 2015 congressional overturn of a bill that banned federal funding of harm reduction work. Under the new administration, Ziegenhorn worries that the ban will be reinstated and that federal funding will disappear.

“A lot of congressional people that represent states where there is a lot of drug use don’t love harm reduction,” she said. “But it works.”

Despite robust federal efforts, Ziegenhorn has encountered significant barriers in breaking down people’s perceptions of addiction.

“Locally, it seems like it takes a lot to get people to think about addiction as a disease, so there’s a lot of work in Iowa to be done around reconceptualizing drug use as a health issue, and not something that is thought of as evil or racially charged, or a criminal issue,” she said.

Many advocates have pointed out similar disparities in public perceptions of drug users. In his 2015 Atlantic piece, Andrew Cohen contrasts the federal response to the current opioid epidemic to their response to the sudden rise of crack in the 1980s. With the crack epidemic, he argues, because most of the affected parties were black, the government treated the issue as a crime, whereas today, when over 90 percent of opioid users are white, the issue is treated as a public health problem.

Similarly, Ziegenhorn noted that despite many drugs’ similar chemical nature, drugs are often categorized by perceived danger, their level of danger often determined by racial perceptions.

“Drug use can be a very classed and racialized thing,” Ziegenhorn said. “Often people separate the use of heroin and meth or crack into a category of scary, dangerous drugs, but treat the use of adderall or prescription opioids or weed or Molly or ecstasy as acceptable…or something you do to help study or have fun at a festival or relax. But there isn’t a true difference between these substances based on their inherent nature as psychoactive substances, we just assign different levels of social meaning to them.”

The roots of what the CDC calls an “opioid overdose epidemic” is not entirely clear-cut. Besides, Ziegenhorn is hesitant to even use the term “epidemic” to describe it, as she says it alludes to a non-causal crisis, when in fact, there are some parties to be blamed—a possible culprit, the pharmaceutical industry. Physicians are often prone to asking their patients if they feel pain, and prescribing painkillers freely according to their answer. This is because, Ziegenhorn explains, pharmaceutical representatives play a large role in educating physicians regarding pain management.

“With what’s going on with opioids, there’s a cause, and someone who directly spread it, and it was doctors freely giving out pain pills everywhere, just because pharmaceutical companies told them to,” Ziegenhorn said.

In March of 2016, the CDC released a report aimed to combat this issue. The report outlined guidelines in prescribing strong painkillers, including when to initiate or continue opioid prescription, the suggested dosage for opioids, and the risks of consumption. However, this alone will not solve the problem.

D

ixie plans to go to college next year, and while she sees a possibility for starting vyvanse again, dealing isn’t something she’d want to do.

“I could see myself going back it [for myself], but not being the drug dealer for it,” she said. “I mean, look at me. No one’s ever going to think of me as a drug dealer.”

A small exception, though: Dixie says she’d consider dealing on a small scale in college, but only if she needed the money. Getting caught up in a larger, more complex drug trade, however, will never be her intention. After all, she says with a laugh, she is “not tough enough for that.”

Abe, too, plans to continue on his current path: he will go to college, and for now, at least, and will continue to use marijuana regularly, as well as prescription drugs, when he can get his hands on them, that is. But his tendencies will persist: he is cautious in trying out new drugs, tries to practice safe usage, and maintains transparent as to why he uses—that is, to get high (‘if you say [you’re doing it for another reason], you’re lying,” he says).

George’s fate is less clear. In the coming year, after graduation, he hopes to travel, do art and make music. Beyond that, George doesn’t know exactly where he will go.

George mentioned that movies about drug users usually end one of two ways: either the main character reaches a “peachy-keen” sobriety, or their descent into drugs takes a turn for the worse, and the movie drops off without resolution. While George hasn’t discounted either of those possibilities for his life, he feels like his path will likely be more nuanced.

“I never rule out the fact that I could overdose. That’s one thing that doesn’t necessarily scare me, but definitely is a reminder, a voice in my head, that at least if I can’t stay sober that I shouldn’t get to that point, he said. “But I could also see my ending being actually peachy, it might be what happens, but often times, it’s just a little harder than that.”

George also sees the possibility of stagnation, for, he says, “there is a certain level of it that goes with using, even if it is casual.” Like Sisyphus, he intends to keep pushing the boulder, yet unlike Sisyphus, it remains possible that George will summit the hill yet.

*Names of students have been changed.