Post-Protests: The Practicality of Civil Disobedience

The Little Hawk editors discuss the uprising of protests internationally, and whether or not they’re really making a change.

Pussy hats were popular at the Women’s March on Washington as well as the sister marches.

February 7, 2017

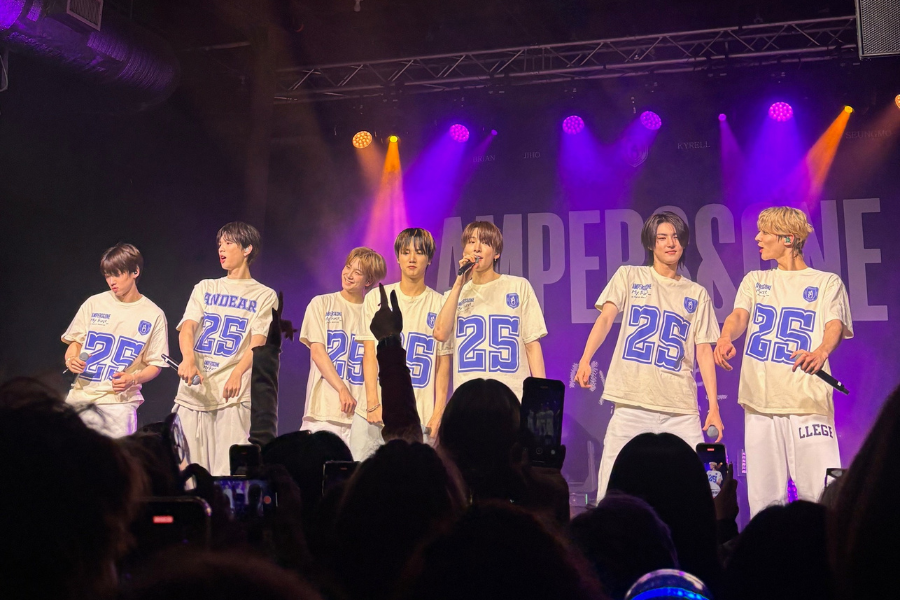

On January 21, 2017, the biggest protest in US history happened in Washington DC. An estimated 500,000 people of all ages, genders, races, ethnicities, and abilities gathered and marched the streets of our capital, and around 2.4 million others joined across the globe. The mantra of “the future is female,” “he will not divide us,” and similar sentiments rocked every form of media. And, while these chants and protests have provided a sense of unity for many in the face of President Trump, they do beg the question, “Are they really working?”

Honestly, there are some pretty valid indicators that the protests have been effective: the ACLU has raised more than $24 million since Trump’s inauguration, and the ban on legal immigrants has been legally challenged.

The First Amendment guarantees us the right to freely assemble: this means that protesting is a fundamental American right. Protests have changed the course of history in the past. During the abolitionist movement, there were protests by enslaved peoples as well as abolitionist allies. During women’s suffrage, there were protests on the capital the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The Civil Rights movement had marches like the Selma to Montgomery march, and the Vietnam War had opposition in the form of student-run protests on campuses. All of these demonstrations and movements called national attention to the issues they addressed — and it was this attention that helped bring about change. Eventually, the 13th Amendment was ratified, and so was the 20th. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was put into law, and (after some time) Nixon announced an effective end to United States involvement in Southeast Asia.

Nowadays, the protests are linked to social media, which allow people to connect and organize in ways that were impossible for earlier generations of Americans. Facebook pages organizing the Women’s March and Anti-DAPL protests allowed thousands to come together across cities, states, and nations, and Snapchat videos gave people the chance to see first hand what went on at these protests. Twitter has given news organizations and bloggers the chance to share their thoughts and experiences with protests, and opposers to whatever movement is taking a stand are able to voice their concerns with just the push of a few buttons.

Now, there are some people who believe street protests as unpatriotic, claiming that our duty is to unquestioningly support the elected president and his policies, or at least to maintain a polite silence and only make our feelings known at the ballot box when we vote. And that’s valid — the democratic process and voting are critical in American politics, and should be respected. But this country wouldn’t be what it is without the protests that have shaped the course of its history in important and progressive directions. Slaves were freed, women got the vote, and wars were ended because of protests.

So, when thousands descended on our nation’s capital to walk the streets in protest of Donald Trump’s policies, they were acting as patriotically as anyone could. Now, we’ll have to wait and see what kinds of social, cultural, and legal changes will follow. We’re hopeful they will break barriers and move the country forward as surely and effectively as the protests of the past. The people have spoken, and they continue to speak — and rally and chant and march — and giving voice to the people is really what American democracy is all about.