New Security Measures May Affect Student Privacy

With the Incorporation of the One-to-One Chromebook Program, Privacy Issues Emerge

November 7, 2017

At the beginning of the 2017-2018 school year, every student from grades 9-12 received Chromebooks from the Iowa City Community School District as part of the district’s One to One initiative.

“Most schools were going in this direction, so the district realized that this was going to need to happen,” said City High principal John Bacon.

As part of the switch, Bacon says the district underwent a comprehensive infrastructure upgrade, increasing things such as internet bandwidth– the amount of data an internet connection can transfer at any given time. They also had to determine what type of security measures to implement so that content would be appropriately filtered on Chromebooks.

“We narrowed our search between two security systems, GoGuardian and Securly,” said Adam Kurth, Director of Technology and Innovation at ICCSD. “We eventually chose Securly for mainly its financial cost, as both systems would achieve the same goal of our district in regards to filtering.”

Securly’s filtering system is based on a large selection of keywords. Some keywords, by federal law, are required to be checked, and some are a matter of district philosophy.

“We talked to the district legal counsel to help us with the legal aspect of filtering in a 1:1 program, and then we decided individually which sites we want to block. Some example of things we chose to block are apps such as Snapchat,” Mr. Kurth said.

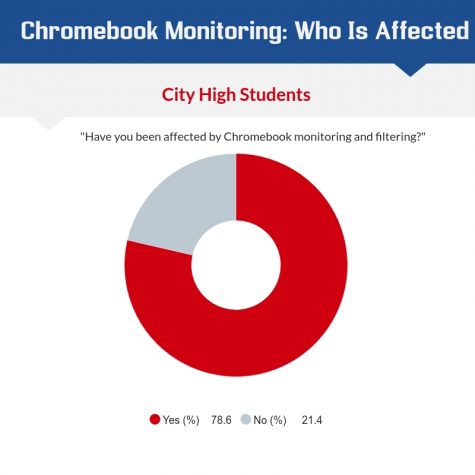

However, some students have reported that some websites have been blocked that they believe are completely appropriate for school.

“I take a medical class and I’m not able to look up certain terms because they are blocked,” one student answered in a Little Hawk survey about the new security measures on Chromebooks.

“Multiple educational Youtube videos were blocked. I checked them on my phone, and there was nothing wrong with them– no swearing, violence, drugs or [similar things],” another student replied.

Kurth says that incidents like these will be looked at by the district, but may not be possible to fix because websites are blocked on a keyword basis.

“We are required to be blocking sites with pornography, drugs, gambling, and sites that have hateful messages,” he said. “However, it is difficult to address these individual instances because each keyword blocks thousands of websites.”

In addition to these security measures, parents are sent an email every month containing websites and keywords their student has searched or visited. One student who wished to stay anonymous felt as if high school students should be in control of their own safety.

“It is completely wrong. We are high school students who can handle whatever we see online,” they said.

In addition to neither students nor parents explicitly signing up for this service, students were never notified that their data would be collected. This non-communication is one of Kurth’s biggest regrets about the program.

“Honestly, if I could change one thing about our 1:1 rule that would be it,” Kurth said.

According to Google for Education, or G-Suite’s privacy policy, Google only shares information with districts or parent companies with user or parental consent.

“We will share personal information with companies, organizations or individuals outside of Google when we have user consent or parents’ consent (as applicable),” says G-Suite’s “Information We Share” section of their privacy policy.

However, students (users) and parents both never consented. Even though minor’s signatures aren’t binding, parents still weren’t contacted about this agreement. The only signature or agreement students agreed to was when they created their Google accounts; and students’ accounts were created by the district. Regardless of whether students did check the box when their accounts were first accessed, many students feel that a district-wide shift to the 1:1 program should warrant another look at the privacy policy. One example of this is Apple requiring their users to agree to a privacy policy each time the user wants to install a new software update; the district could do the same with Chromebooks.

“I think that whenever there is a change in systems, a user would be required to agree to a privacy policy that details the new features of the system that might interfere with my privacy,” said an anonymous student.

Privacy has long been an issue with districts who switched to 1:1 programs. In Rhode Island, the Lower Merion School District was found to have taken over 50,000 photos of their students using their school owned computers’ built in camera’s. An EFF (Electronic Frontier Foundation) study found among a study of 1000 school system members that “45 percent of parents reported that their schools or districts did not provide parents with written disclosure about ed tech and data collection”. That same study also found that 57% of parents responding to the study were “completely sure they had not received written disclosure about their school’s ed tech practices”. ICCSD broke this trend, as parents with a kid in any district high school were notified about this email before the school year started.

“I believe we were sent an email by Mr. Bacon, and then by the district about these emails,” said Izaskun Lejarcegui, parent of City High student Bihotza James-Lejarcegui ‘18.

Post implementation, Mr. Kurth wishes that the amount of communication between the district and students could’ve been more distinct and frequent.