Staff Editorial: Coded

Despite purporting to protect the learning environment, dress codes harm more than they help.

February 16, 2018

When student Eric Thomas ‘18 won the annual ugly sweater contest in December, sporting a homemade contraption comprised of several pairs of socks and gold shorts, the City High gymnasium erupted into applause. Thomas got a handshake from Principal Bacon and a Pancheros gift card from the administration. But behind that celebration was a truth uglier than his makeshift sweater: No female student could have ever gotten away with what he did.

To be fair, this is not a criticism of Thomas. The energy and dedication he brings to the spirit assemblies deserves recognition. Rather, this is evidence of the inherent flaws of the system that rewards him and punishes girls for walking around school halls with a bra strap showing.

“As a white male I’m probably a lot more privileged than the average person,” Thomas agreed. “I heard that there was a couple of people that got dress-coded right after I was basically naked in the gym. It’s really stupid that that happens, but I don’t know how to fix it.”

Like Thomas, Beatrice Kearns ‘19 is no stranger to dress code enforcement.

“[In junior high] I was sent to the office because I refused to change because I said that it was sexist,” Kearns said. “There was a boy sitting right next to me in a very similar tank top and the teacher said nothing.”

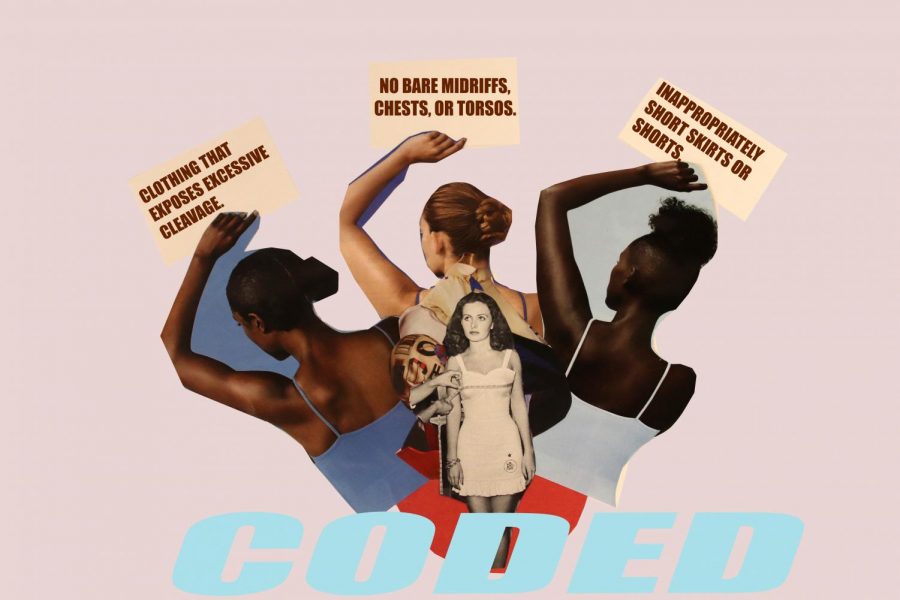

In recent years, dress codes have been the subject of heightened scrutiny due to the perception that they unfairly target female students. Not only are these codes disproportionately enforced upon girls, but they are also written to target female students. Take City High’s dress code: While most rules are applicable to all students, several rules pertain specifically to female students, who are required to limit “excessive cleavage” and “inappropriately short skirts.” There are no corresponding rules for male students.

Like many students, Kearns feels that the difference in these standards could be damaging to the women and girls at school.

“At Southeast, I found the dress code to be extremely sexist and oppressive,” Kearns said. “It reinforced the idea that women and girls are objects—and sexual objects, at that.”

Kearns described a specific incident when she pointed out problems in the school dress code and was punished for it.

“I said that I thought the teacher was being sexist and she sent me to the office,” Kearns said. “I actually almost got suspended because of this.”

School officials often defend dress codes as a way to create a proper learning environment. They cite the bare shoulders or midriffs of female students, usually underage, as ‘distracting’ to men in the vicinity. Not only is this a view that holds women accountable for the actions of men, it prioritizes men over women. In order to supposedly protect male students’ educations, women are forced to change clothes, miss classes, or even get sent home altogether. This system criticizes girls for ‘taking away’ from male learning while simultaneously disallowing them from the safe, productive learning environment it purports to defend. In this way, dress codes hurt young women by prioritizing their bodies—and men’s reactions to them—over their minds.

Furthermore, the positive impact these codes have on the learning environment is debatable. When Thomas was asked about whether he found it hard to concentrate because of the way that female students dress, he laughed.

“Not really, no,” he said. “It’s not distracting at all.”

Kearns is already working to change the dress code system. Following her near suspension, she and Maya Durham ‘19 spearheaded a protest at South East.

“At the end of eighth grade, we all went to school wearing tank tops. We figured that there was strength in numbers and that they weren’t going to send all of us home,” Kearns said. “The year after we left, they actually ended up changing the dress code, so I’d say that we made a positive impact.”

Often, the brunt of these issues falls on specific categories of women. Because dress-codes establish a narrow standard for how women express themselves, they target any student who doesn’t conform to ‘normal’ femininity. That traditionalist femininity often means being ‘modest,’ thin, and white. Plus-size women, who are more likely to be showing cleavage or larger amounts of skin while wearing similar clothing to others, are more likely to be dress-coded because of their body shape. This stigma can disproportionately target students who, because of the beauty standards they see in our culture, may already be less comfortable in their own skins.

In addition to plus-size women, dress codes are often more heavily enforced on young women of color. A 2017 report from Georgetown University found that black girls ages 5-14 are perceived as older and more sexually mature than their white peers. This discrepancy is partially responsible for the discipline gap between white and minority students, especially in terms of dress code enforcement. Likewise, trans* students face a similar burden, limited by the sex on their birth certificates and perceived as non-conforming even when they follow the code to the letter.

Schools may feel that they have a responsibility to police the way students dress, but they also pledge themselves to protecting and providing a safe learning environments for all students no matter who they are, what they look like, or how they identify. City High’s nondiscrimination policy states that they shall not “discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, religion, creed, age, marital status, sexual orientation, gender identity and socioeconomic status in its educational programs, activities, or employment practices.” In its current form and enforcement, the dress code violates that pledge. No code that explicitly targets certain students and implicitly harms them though biased enforcement can hold up to that promise. For that reason, the district should reevaluate the code or at the very least its enforcement.

City High is a place where students should feel secure. It is a place where students should be able to express themselves in the best and truest ways they can. That’s what we’re told. That’s what it says on the tin.

How long until we hold ourselves to it?