Double Standards

A one-two punch on the definition of terrorism and unequal media coverage in America

April 11, 2018

In the beginning, terror meant one thing, and one thing only: fear.

The word ‘terror’ came into English in what is, when one considers the tortuous and complicated paths etymology often takes, a very direct manner. The word came by way of Old French from the common Latin verb terrere meaning “to frighten.”

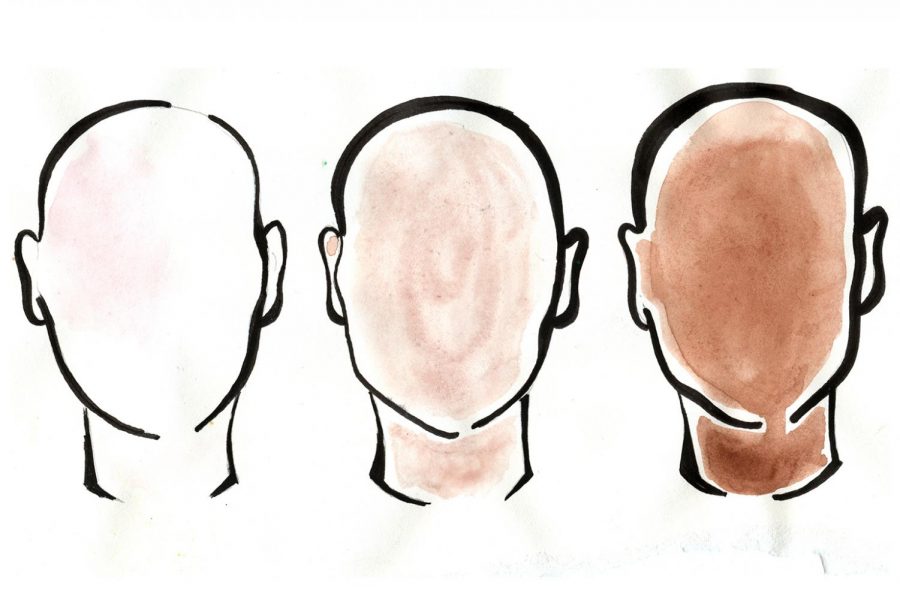

One might not guess that a word with such a simple meaning would exert such force over today’s America, or that it would be possessed of such specific connotations. In this country’s mainstream perspective, terror means Islamic extremism. It is an amorphous entity. Except in rare cases like 9/11, it does not strike at home. It is not made from people, but rather from some evil that justifies war. When Americans (especially white ones) think of terrorism, what they see may be many things, but it is probably not white men. It is probably not white men with guns.

Yet according to CNN, “For every one American killed by an act of terror in the United States or abroad in 2014, more than 1,049 died because of guns.”

By now, everyone in this country has probably heard from at least one student who says that they are scared of going to school because of the threat of violence hanging over their head. Observing this widespread paranoia and trepidation in our nation’s children, it is difficult to see why we do not term mass shootings terrorism. If terror at its core, at its most distilled, is only fear, then of course mass shootings are terrorism.

There is one main reason that mass shootings are not generally called acts of terror, and that reason is their demographics. According to Newsweek, a majority—54%—of mass shootings are committed by white men. Calling them terrorist acts would be redefining white America’s conventional image of terrorism as something racially or religiously charged, as something other. Calling them terrorist acts would be exposing that the real threat to America is coming not from foreign threats, not from people of color who can be ostracized and dehumanized, but from the very demographic that is constantly given the benefit of the doubt: white men.

Unequal media coverage based on demographics is nothing new for this country. Over the past few decades, white male shooters have been humanized, given backstories to justify their actions, or depicted as ‘tragic geniuses,’ as sensitive, shy individuals, victims of a cruel world order which just couldn’t seem to fit them in.

These depictions may be slightly different, but they all have one thing in common: humanization and justification of white shooters and their actions. Tucson shooter Jared Loughner’s possible mental illness and “troubled life” were parsed and analyzed by Time Magazine as the driving factors behind his murder of 13 people and attempted murder of six others in January 2011. Discourse on James Holmes, who killed and injured a total of 82 people in a movie theater in Aurora, CO, described him as socially awkward and intelligent, as well as “a typical American kid,” despite the fact that Holmes was 24 at the time of the shooting.

Dylann Roof, who killed nine black people in a church in Charleston in 2015, was a self-professed white supremacist. Roof declared that he wanted a “race war” and pictures emerged of Roof wearing a patch on his jacket which displayed the flag of Apartheid-era South Africa. Still, Senator Lindsey Graham linked his violence to hatred of Christians rather than of black people. “There are people out there looking for Christians to kill them,” Graham said, disregarding Roof’s own assertion that his shooting was racially motivated and testimonials from his peers that he was segregationist and racist.

Meanwhile, people of color victimized by police are frequently demonized. Trayvon Martin, who was unarmed when George Zimmerman shot him, was wearing a hoodie which ultimately became his most important trait in the coverage of his murder. Michael Brown, the Ferguson, MO, victim whose shooting sparked nationwide outrage, was described as ‘no angel.’ Megyn Kelly said that Dajerria Becton, a fifteen-year-old black girl violently arrested by a police officer at a pool party, was ‘no saint.’ Tamir Rice, a twelve-year-old black boy, carried a BB gun and a police officer shot him twice in the chest–after which the police force described him as a ‘young man.’ But 19-year-old Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz? A ‘troubled kid.’ We call a man who entered a school and killed seventeen of his classmates a kid, while we demonize children and adolescents of color who are victims of police violence. Looking at these cases critically, one begins to see the clear divides—the clear priorities—of the American media.

All of these angles, all of these segregated justifications and dehumanizations, add once again to the concept of “otherness” pervasive in coverage of terrorism. White America depicts shooters as loners, as individuals who acted completely of their own accord, in the hope of dissuading citizens from seeing that systemic violence is a problem, that the greatest threat comes from within.

We are told that terrorism is committed by people of color, that their violence is a phenomenon linked to gangs or organizations like ISIS. When it comes to threats to our society, what we see may be many things, but it is probably not white men. It is probably not white men with guns. Because not all white people are terrorists, no white people are.

The thing is, America, not all people of color are terrorists either.

We must work our magic and our justice in solidarity. We must be all or nothing, because terror means fear, and we are all afraid–but not of them, of the nameless, racially segregated “other” as this society has tried so hard to make us. Instead, we are afraid of this fractured, angry, tragic, genius, sensitive, shy, lonely, troubled, violent, human, inhumane country we all call home.

In America, we are not now taking our lives in our hands. We have had them tight in our fists for years, smashed up against our passivity, our inaction, and our weak justifications of hatred, of “terrorism” as Islamic extremism, of “thuggery” as something possessed if and only if one is black. Like children (like our children, like the ones we have lost to bullets), we have clutched these outdated monikers to our chests. Like children, we have not given them up.

In the beginning, terror meant one thing, and one thing only: fear.

It’s time to let go.