The Year of the Woman: Empowerment and Decimation

2018 has seemingly been full of successes for women, but it has also been full of horrors. The Little Hawk editors investigate this dynamic.

September 25, 2018

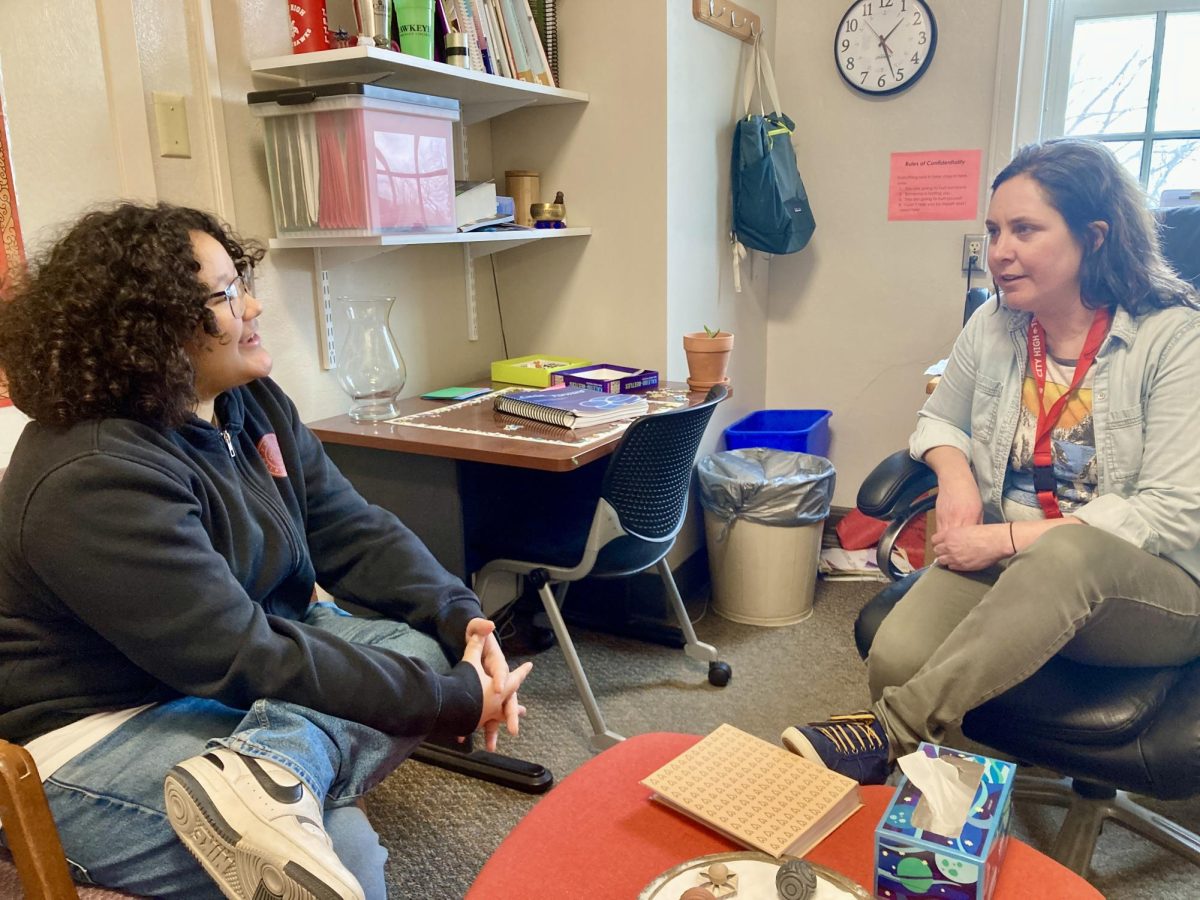

On January 21, 2017, an estimated four million Americans protested the beginning of the Trump presidency in what was known as the Women’s March. Over a year and a half later, the momentum from that day is still being carried on in every aspect of American life, from national politics to City High.

Beginning in the fall of 2017, the #MeToo movement reset what was and was not acceptable behavior in the workplace. Following accusation after accusation, hundreds of people guilty of sexual misconduct lost their jobs or the respect many had for them. The truth was finally being revealed about abusers, from co-founder of entertainment company Miramax Harvey Weinstein, to former CBS CEO Les Moonves. The tolerance for those with power abusing it for pleasure and intimidation no longer exists in our society, and that has allowed those who used to be kept from power, to rise to the top on national, record-breaking levels.

The midterms of 2018 are reinforcing the cries that 2018 is the Year of the Woman with ground-breaking nominations and record-breaking numbers. 256 women have been nominated for the elections in November so far: 234 for the House and 22 for the Senate. That total of 256 is made up of 197 Democrats and 59 Republicans. 234 women as nominees for the House is almost double the previous record of 120 in 2016, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers.

Those nominees are not only hitting new milestones in gender-oriented numbers, but they’re also breaking barriers in many other aspects of identity. Former Democratic member of the Michigan House of Representatives Rashida Tlaib is running unopposed to become the first Muslim woman ever elected to Congress. Also running to become the first Muslim woman ever elected to Congress is Minnesota state representative Ilhan Omar, who became the first Somali-American Muslim elected to office in 2016.

Beyond race and religion, Gina Ortiz Jones is running to become the first woman to represent the 23rd Congressional District of Texas—the first Filipina-American elected from the district, and the first openly lesbian member of the House.

Even outside of those 256 candidates for Congress, history is being made. Stacey Abrams, former minority leader of the Georgia House, is running to become the first African-American woman governor in American history. In the offices, industries, and government within the United States, change is upon us. Even room 2109 is not immune to this change: this year, the editorial board for the Little Hawk is completely made up of female students.

But in other ways, equality isn’t coming so easily. In the past two months, two young women have been murdered in Iowa, garnering intense media attention. Mollie Tibbetts’ disappearance and murder became a nationwide tragedy, calling attention in every corner of the country, from missing posters in Iowa City businesses to a video made by President Trump. Celia Barquin Arozamena, a golf star at Iowa State University, was murdered on a golf course, and her death caused outrage in Iowa, as well as immense grief to those who knew her at ISU and in her native Spain. (It should be noted that the death of Arozamena, who was allegedly killed by a white American citizen, was not close to as publicized as that of Tibbetts, allegedly murdered by an undocumented immigrant with Mexican citizenship, around which fact President Trump’s video mourning her death centered.)

The deaths of these young women, and the circumstances surrounding them, remind us of a sobering truth: progress drags its heels. Those editors in room 2109 have been told to carry pepper spray, have been followed, have been harassed and catcalled and made frightened and angry, made to feel lesser. In the Year of the Woman, our world has shifted in big ways, but in the small ones it feels disappointingly similar.

Around the world, violence against women is still a very real problem. In conflicts such as those over religious divides, like the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar, many women are molested and killed. Even in times of peace, domestic violence affects predominantly women in vast numbers; according to the World Health Organization, 35% of women worldwide have experienced domestic violence. Women everywhere are still being harassed and catcalled and made frightened and angry, made to feel lesser. These problems won’t disappear immediately when we elect a record numbers of congresswomen; these problems won’t disappear at all if we do not continue to take action.

There is every reason to be hopeful. Domestic violence against women is going down (72% from 1994 to 2011, according to CNN); women’s rights in the workplace and in society are being brought to attention and advanced; the representation gap in politics is slowly being closed. But these divides, these systems of oppression still exist in our world today, and complacency will not solve them; only a concerted and passionate collective effort for change will help us achieve equality. The Year of the Woman is the year that women excel in politics, indeed, but it can also be the year we make things better for all women, everywhere. It can also be the year we rise once more and fight. We must put women on cabinets and benches and seats in government, and we must put women on equal footing. The Year of the Woman is our year: to win, to celebrate, but also to continue the work this world needs.