Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

Black students over five times as likely to be suspended as white peers in the ICCSD

City High School is part of the Iowa City Community School District, or the ICCSD.

December 20, 2019

Malcom* was playing with a BB gun. He was with two friends, but they are white, and he is black. They shot at a shed, and then the cops came. Malcom served 17 months and his friends served no time. What Malcom never knew was that

he had been on the track to incarceration since kindergarten.

“[I’ve been suspended] from kindergarten through freshman year,” Malcom said. “It was all the little things. Hopping the fence to get the ball or [getting into] arguments with teachers. It got to the point where I had my own designated spot in the office because they suspended me so much for little things. And then, obviously, I’d start getting annoyed and start building my anger. And it progressively got worse.”

Malcom hasn’t felt trusted at school since he was a child, and he still feels untrusted at City.

“[Feeling watched] made me feel like I couldn’t be trusted at school,” Malcom said. “I should feel like I can walk through the hallways and not have to look over my shoulder. The hall monitors pop up on me random times. They’re looking for me.”

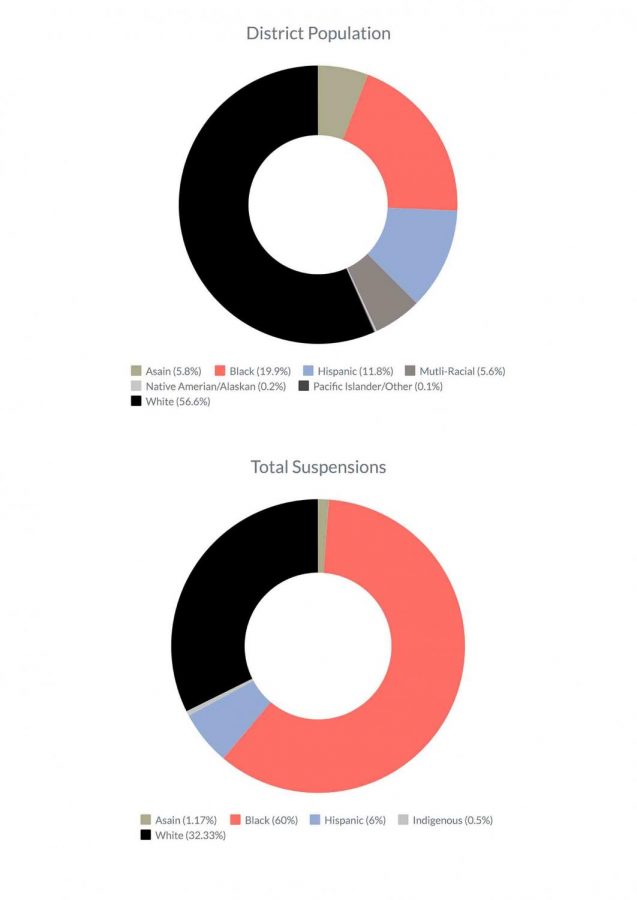

The United State’s criminal justice system is the largest in the world. Iowa is third worst in the nation for back vs. white racial disparities in prisons, according to a study on the U.S. Bureau of Statistics by the Sentencing Project in 2016. These disparities also affect City High. Black students across the district account for 20 percent of the district’s student population and 60 percent of both in- and out-of-school suspensions.

“The way [staff] treat black men at City High is ridiculous,” a black student at City said. “It’s absolutely ridiculous. And we always love to talk about how we’re the school that leads, every student has an equal chance of success, all of that good stuff. But unless you’re a student athlete, and even if you’re a student athlete, your life [as a black man] is treated as if you’re always on the verge of doing something wrong. People will literally walk down the hallways, and if they see a black boy walking down the hallway will stop them to ask where they’re going, what they’re supposed to be doing.”

In an effort to address issues related to race, the district staff is currently undergoing a two-year implicit bias training.

“Being suspended a lot of times is up to the judgment of hall monitors and teachers,” Franklin Hornbuckle ‘20 said. Hornbuckle has received one detention, and he was the only white person in the room. “If you have implicit biases toward African Americans or minorities, then tiny judgments [by hall monitors and teachers] make a huge difference on whether or not they decide the students are up to bad things.”

The bias of individuals beyond school staff plays a role in a student’s chances of being suspended or even incarcerated. The bias of school staff, police, lawyers, and judges affects whether or not minors make it into the prison system. When Karen*, a Caucasian student at City, was illegally smoking marijuana with friends, they were spoken to by a Caucasian policeman.

“I put my hands up,” Karen said. “It was very clear that we were smoking weed because there was a pipe, a lighter and weed on the table. We looked very high. I repeated multiple times, ‘Please don’t tell my mom.’ I felt very sure that I wasn’t going to get arrested. The thought never crossed my mind. I felt safe.”

Karen has also been high at school numerous times, and she did not fear consequences at school or in the presence of a policeman.

“I was never scared of being suspended, expelled, kicked out, or even [getting] detention,” Karen said. “I was always thinking, ‘This teacher is going to think poorly of me,’ or, ‘They’re going to tell my mom during conferences.’”

Karen was not caught** for being under the influence at school, and when she was caught by the police she received a warning. A charge for possession of marijuana would not have incarcerated Karen, but it could have hindered her participation in school events like sports and clubs.

“I’ve had friends of color who were suspended for things that my white friends have done, gotten away with things, and never had to face the consequences,” a black student at City said. “People show up to school high all the time.”

When Karen was under the influence at school, she said she felt comfortable because she thought her teachers would not report her. And they didn’t. Clarissa*, a black student, was not so lucky.

“A student pointed at me and then [the teacher] had me reported,” Clarissa said. “We went down to the office and they searched my backpack, but there wasn’t anything in there. They were basically telling me how they could call the police on me. I didn’t know what to say. I knew what I did, so I couldn’t complain about any consequences.”

Clarissa received four days of suspension total after the incident. Once she was back in school, staff members spoke with her about how she could still participate in her sport despite having been suspended. Staff discussed how she could start the season earlier in order to fully compete in the sport. The district’s policy on events like this is included in its good conduct policy.

“Black, brown, green, or whatever, we have a code of conduct here at City High that we follow for athletic suspensions. It is the same as when a student gets an F in a class. The rules [are] the same,” Gerry Coleman, dean of students at City High, said.

If a student is suspended in or out of school, the administration decides which level of offense that suspension belongs in within the good conduct policy. Once the administration decides the level of the suspension, coaches must abide by the punishment that follows it.

“Once that decision is made the coach has to honor that,” John Bacon, principal of City High said. “I couldn’t more strongly defend our record on good conduct penalty’s enforcement. If there is a documented, clear-cut case that meets the threshold of the good conduct penalty, it is enforced 100 percent of the time. People can say things and they’re there. They just have a misunderstanding because the reality is that there are things that our athletes may do and get away with, unfortunately.”

Despite the administration’s belief that the good conduct policy is consistently enforced, some students still believe athletes can avoid serving full penalties for drug-related offenses.

“I think sports-wise, I don’t know that everyone has the same consequences,” Clarissa said. “I know [REDACTED, a student athlete at City] has definitely been caught multiple times doing stuff and they’re still participating in their sport. I was at a party with [REDACTED] this summer that got busted. I left before it got busted, but they were still there and their mom talked to the police so he could do his full sports season.”

Caucasian students are 56.6 percent of the district’s student population and 32.3 percent of total suspensions.

“They can’t drug-test [a certain City High sport team] because these [athletes] will continue to do drugs,” Karen said. “The school has a good [sport] team, and we like that type of thing. I think that if a student brings something that the administration sees as valuable to them, then they will allow students to do things that they otherwise would receive harsher consequences.”

There are many causes for the disproportionality in suspensions. In order to be suspended, students are first reported by their teacher, a hall monitor, or a fellow student, but not all teachers, hall monitors, and students report their suspicions. This is sometimes due to personal beliefs and sometimes due to lack of trust in the administration’s response to reports. This means that student discipline is at the discretion of individuals.

“When it’s tangible, when it’s smoking weed, it’s vaping, it’s punching someone right in the nose; that is concrete, more than it is if you’re bullying someone,” Scott Jespersen, City High’s assistant principal, said.

In addressing the multitude of potential causes of the discipline disparities between white and black students at City, the school turned to the work of Ruby Payne, a white woman who works in education leadership.

“[Payne’s] theory was that sometimes with African American students and white teachers, there is a culture difference,” Jespersen said. “Some of it is spatial, some of it’s volume, different things. But I don’t think you can take one thing and say, ‘Oh, that’s why [the disproportionality is there].’”

The issue of representation in City High’s staff came up numerous times in a staff meeting in November 2019 where students spoke to staff members about bettering the school. Despite pressure from students and families, the district has yet to hire more teachers of color.

“Our staff doesn’t look like 40 percent of our students,” Jesperson said. “As somebody that helps hire all the teachers here, we’re not seeing [African American] applicants for our positions.”

Finding solutions to an issue like racial disparities is undeniably difficult. Latasha Deloach, the vice chair of the Iowa Disproportionate Minority Contact Committee, a subcommittee of the Juvenile Justice Advisory Council, believes this topic becomes even more complex when white individuals run the institutions that contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline.

“You have people who are running the school who’ve never had those experiences,” Deloach said. “[Administrators] only hear about [struggling students] and they feel bad for them. They have pain in their hearts for them. But they’re looking through a looking glass. [Administrators] are looking in like, ‘Man, that looks rough over there,’ but they have no idea what it is like. They don’t know what that hustle is like. Where [students are] trying to figure out what [their] next meal is coming from, or how [they’re] gonna make sure [their] brothers and sisters are cool. If you don’t know that life, if it’s just something you’ve read about, then you don’t understand why people make the choices that they make.”

The real cause of the disproportionality could be many things. Whether the staff doesn’t look like the students and there’s a ‘cultural difference,’ or teachers aren’t consistent in reporting students bad behaviors, Deloach believes the root of the issue is something no one wants to talk about.

“We ask why there are so many suspensions, but we’re not looking at the core reason of what leads to these things: racism,” Deloach said. “We don’t want to talk about that.”

When interviewed, Jespersen did not mention racism as a potential reason for the disproportionality or lack thereof.

“I don’t think our data is disproportionate anymore,” Jespersen said.

However, many students of color at City feel like they are watched more than other students in school and in the community.

“Everybody in town kind of got that eye on me because I’m that big black man around town,” Malcom said. “Because I’m [a] six foot two African American teen. And people are fearful of that.”

Malcom has never felt like anyone was truly fighting for him. Almost no one was fighting for him in school, in court, or prison. The only person fighting for him, he said, was his mom and one resource officer in eighth grade, but it wasn’t enough. 17 months of his life were spent in rehabilitation centers where he was verbally and physically abused. A staff member at one center grabbed, pulled, and stepped on Malcom’s leg while his knee was broken, all without repercussions.

“They tackled me down to the ground,” Malcom said. “I got scars on my body from just the restraints. I got this big one here on my arm from a door because they tried to throw me in a room and my arm was sliced by the door.”

Some members of the black community purposely or inadvertently attempt to avoid situations like Malcom’s by immersing themselves amongst their white peers.

“When I was a student, I saw other girls going through it,” Deloach said. “I had the advantage of growing up to the age of nine in Iowa, so I grew up in predominantly white spaces. I had years of studying white people to learn how I need to perform, to stay out of trouble. I knew how to assimilate enough to stay under the radar. I knew the rules, those invisible rules that no one talks about. I know about how my blackness is not acceptable in those spaces.”

According to a report by the ACLU on U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection, in Iowa, black girls are nine times more likely to be arrested than white girls.

“I saw [a hall monitor] physically [grab] a black boy who tried to cut in line at lunch,” a black student at City said. “He grabbed him by his arms and dragged him out of the line. He was being extra aggressive. The person wasn’t even resisting. They were like, ‘Yeah, yeah, I get it. Okay, bye.’ And then, right there, [a hall monitor] escorted [REDACTED, a Caucasian student] right to the front.”

The district has made efforts to counter issues surrounding racial disparities in suspension and discipline throughout the district, but Deloach says the solution is more about student’s mental health than their race.

“To find a solution, I think we have to look at the human condition of our kids,” Deloach said. “Kids just want spaces in their school where they can go and seek help when the day was too much.”

The recommended student-to-counselor ratio for schools in the United States is 250 to 1, and according to the U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection, Iowa’s student to counselor ratio is 378 to 1. Only three states meet the recommended ratio.

“[The district] has other things in their hand that they think is a bigger priority, which means that it’s not really student first,” Deloach said. “It means you have to go back to the mission of the district. It’s more about education and global leaders than, ‘We’re gonna send you out there educated but you’re going to be emotionally deficient. You’re going to be able to do all these amazing things and get all these great grades in school but you’ll have a higher chance of suicide.’ We know that we have a mental health crisis. We know the answers. And we know the solutions. We just choose not to pay for them.”

*Students’ names were changed to protect their anonymity as minors.

**Clarification: Karen was never caught at City High for violating drug policies. Her warning by a police officer quoted in this story happened off school grounds.

City High administration has followed student code of conduct for all students they have caught violating the code for drugs or fighting.

***A correction to the original title: black students are not two times more likely to be suspended than their white peers, they are over five times more likely to be suspended.

Bri • Mar 22, 2022 at 10:40 am

This is really well written!

Kenneth Mcphaul, Jr M.Ed • Oct 2, 2020 at 3:58 pm

This is what happens when the teacher’s in our schools 87% white females. Many use the code of conduct to steer our students to Prison pipeline from kindergarten. As, a retired Urban High School Principal, it is either Special Education or suspension. The chemical companies are behind this with the pushing of Prozac, Ritalin and Zoloft.

Penny Kittle • Jun 21, 2020 at 10:23 pm

Terrific work. I will be using this article as an example in my freshman composition classes this fall at Plymouth State University. This writing takes us inside student stories right from the start. Smart organization and passionate work. I look forward to reading more of your writing in the future.

Roby • Jun 17, 2020 at 1:27 am

Thank you Nina for being this inspiring and congrats too for the NYT acknowledgment !

All the best, Roby

Patti • Jun 11, 2020 at 9:40 am

Nicely written! Your article manages to bring up several key points on the disparities of our society better than many emotion driven articles I have read from more experienced journalists. Keep up the good work and Congratulations for your well-earned award!

Rue • Jun 9, 2020 at 3:49 pm

This article was so informative. Thank you for this.

HYENJIN CHO • Jun 9, 2020 at 4:05 am

Hey, I found your article through an article from the NYT. This is really great work! I hope you keep providing the world with more provocative and insightful journalism. ~A fellow student journalist from Korea

mori • Jun 8, 2020 at 1:03 pm

Go Little Hawk!

Congrats to Nina and The Little Hawk for the recognition for your investigative journalism (just read in the NYT).

-mori class of ’67

Heyishi Zhang • Jun 8, 2020 at 3:28 am

Came here from the times article! This is thorough and brave reporting. Great job! from Canada

Mark Patterson • Jun 8, 2020 at 12:44 am

Admirable reporting. Your timing in researching this is prescient, and it contributes thoughtfully to our country’s consciousness five months later.

(Perhaps I am missing something about the math in the headline. From your statistics, it seems the ratio of black students’ to white students’ rates of suspension would be more than five times rather than nearly double?)

Nina Lavezzo-Stecopoulos • Jun 8, 2020 at 10:55 am

Thank you so much! And yes, embarrassingly we did the math wrong. I will change it ASAP.

Shinhee • Jun 7, 2020 at 11:54 pm

Brilliant work! Thank you for reporting on this important issue. Huge congratulations on the award.

Jane J • Jun 7, 2020 at 10:41 pm

Congratulations!!! This is a well researched, thoughtful article on a very complex topic… looking to reading great things from you in the future!

Tim Kaldahl • Jun 7, 2020 at 10:01 pm

I’ve been a fan of the Little Hawk going back to when I was a high school journalist back in the 1980s. The NY Times brought me here. This story is just great and deeply reported.

Brian Aldous • Jun 7, 2020 at 9:19 pm

Congratulations on you award. Great article; nice mixture of strong research, personal stories to bring it home to readers and timeliness. This is exactly what people are demonstrating in the streets for: equal justice for all.

Kevin T • Jun 7, 2020 at 8:56 pm

Congratulations on this amazing work! Keep it up!

Connor Sephton • Jun 7, 2020 at 7:52 pm

I read about your award in The Times. Congratulations on your excellent reporting. I do hope you consider journalism as a full-time endeavour! Connor, London

Jason • Jun 7, 2020 at 7:44 pm

Although black students account for nearly twice as many suspensions as white students, black students are actually over five times more likely to be suspended than white students.

For example, if there are 100 students and 100 suspensions, based on your statistics, then 20 black students were suspended 60 times while 57 white students were suspended 32 times. On average, each black student was suspended 3 times while each white student was suspended 0.56 times, thus black students are 5.3 times more likely to be suspended than white students.

Nonetheless very informative reporting, keep it up

U.Khan • Jun 7, 2020 at 5:42 pm

Congratulations on being awarded Robert F. Kennedy human rights award! Great work!

Stavros Macrakis • Jun 6, 2020 at 11:20 am

Um, it would be nice if somewhere in the story it had a byline saying where it was from. On the big wide Web (I got here from Twitter), no one know what the ICCSD, The Little Hawk, or SNO is. Yes, of course I Googled it, but that shouldn’t be necessary.

Nina Lavezzo-Stecopoulos • Jun 6, 2020 at 1:32 pm

I will update the deck! Thank you!

Barbara Gerber • Jan 24, 2020 at 10:33 am

My journalism class at Santa Fe High School (New Mexico) says this story is “fire.” Thank you for your excellent and inspiring reporting.