Your donation will support the student journalists of Iowa City High School. For 2023, we are trying to update our video and photo studio, purchase new cameras and attend journalism conferences.

One in a Million

December 20, 2019

A chronic illness is defined as a disease lasting three months or longer, typically incurable and ongoing. Approximately 133 million people have chronic illnesses in the United States according to the National Health Council. Of that 133 million, 30.3 million have diabetes, according the CDC. Chronic illnesses such as diabetes and anemia aren’t easy to deal with. However, they aren’t uncommon. The experience of a chronic illness is much different when it’s rare. Among the people living with a rare disease, two are students at City High.

Sophia Wagner ‘22 was diagnosed with Addison’s Disease the summer after fifth grade after persistent vomiting and migraines. By this time, Wagner had been diagnosed with hypothyroidism, an underactive thyroid gland which can affect body temperature, heart rate and metabolism, and undergone surgery for a heart murmur.

“That summer it kind of reached a point where, looking back on it now, I had gone into crisis for Addison’s disease,” Wagner said.

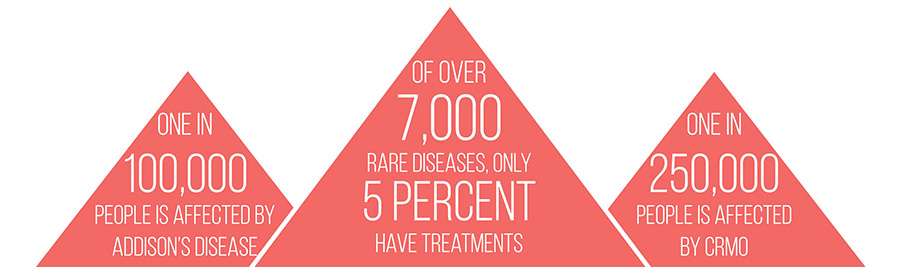

The disease affects the adrenal glands, resulting in a lack of cortisol, the stress hormone. It affects 1 in every 100,000 Americans, according to the Cleveland clinic.

“There were times when I couldn’t get out of bed because I was just so weak that I couldn’t even stand up,” Wagner said.

Rebecca Michaeli was diagnosed with CRMO the summer after second grade after recurrent fevers, which eventually spiked around 105 degrees Fahrenheit.

“I went through three pediatricians, two infectious disease doctors, and orthopedic doctors, and they all disagreed with each other,” Michaeli said. “They couldn’t figure out what it was; they had never seen anything like it.”

CRMO is an inflammatory bone disease that affects 0.4 out of every 100,000 people yearly, according to the American College of Rheumatology.

“It was scary from the beginning, but as soon as the doctors started disagreeing and saying they had never really seen anything like it, that was when it was really scary,” Michaeli said.

Fighting a Rare Illness

In the United States, a disease is qualified as rare when it affects fewer than one in 200,000 people. In other countries, like the European Union, a rare disease is anything that affects less than one in 2,000 people, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In both cases, the rarity of the illnesses made them difficult for doctors to diagnose. This caused Wagner to originally be misdiagnosed with a gluten intolerance. During another visit with a physician at her doctor’s office, Wagner was told she had the flu and sent home.

“If I had [gone] home [thinking] that I had the flu, I would have died. However, since I had the doctor at the University, my mom called that doctor, and they sent me in for tests,” Wagner said.

After Michaeli was admitted to the hospital, her grandparents, both doctors, flew from San Francisco, California, to Iowa City to be closer to the family. Michaeli’s grandfather, Dr. Dov Michaeli, has spent a large portion of his career doing research in his lab at UCSF. He does not practice medicine anymore, but enjoys writing for a blog called “The Doctor Weighs In” and was also able to look at the case from a researcher’s perspective.

It wasn’t until 10 days after being admitted that Michaeli had been given a diagnosis.

“No one knew what was going on,” Michaeli said, “The whole time before they figured it out was probably the scariest time.”

However, the doctor who discovered the gene for CRMO, Dr. Polly Ferguson, happened to work in the same hospital at which Michaeli was being treated.

“Dr. Ferguson was down the hallway. [She is] one of the only doctors in the world who studies [CRMO],” Michaeli said. “People fly from all over the world to see her and I think the ironic part is that she was a hundred feet down the hallway from my hospital room.”

In Wagner’s case, once she was diagnosed, it was partially credited to the yellowish tint of her skin, a symptom of Addison’s.

“I was a kid who…I guess to me, it just felt like I was sick, and I didn’t realize at the time how bad it actually was,” Sophia said. “I was used to [it] at this point—that sounds really sad, but I was used to having to go to a hospital and get tests done. Nothing, thus far, had been super life-threatening. So for my family, [the scary part] was definitely the whole diagnosis process.”

Both illnesses are increasingly becoming less rare. However, this could be due to a rise in awareness. When diagnosing Addison’s, doctors are learning to look for more obvious signs.

“With Addison’s, one [theory] is that it is awareness rather than it truly becoming more common, doctors now have better tools to diagnose it,” Dr. Michaeli explained. “The diagnostic tests are much more assertive, the imaging and all those things. The other [theory] is that it may be environmental. We don’t know that for sure but environmental, meaning pollution and all kinds of chemical data in the environment.”

Dr. Michaeli feels that it’s the rarity and not the severeness of the illness that makes it serious.

“[CRMO] is a one in a million disease,” Dr. Michaeli said. “The other interesting thing is that girls get it five times more frequently than boys.”

Wagner was a part of a case study at the University of Iowa, presenting to medical students in order to raise awareness.

“People are uninformed about it. In fact, also, Addison’s is known to mimic other diseases,” Wagner explained. “They actually tested me for it. They tested my cortisol levels at one point and I was fine for them, so they ruled it out.”

According to America’s Biopharmaceutical Companies, there are over 7,000 rare diseases, most of which are life-threatening, but only 5% have treatments.

While both Michaeli and Wagner are treated and have their illnesses under control, they still feel the effects.

For Michaeli, she has been in remission for years, meaning signs and symptoms of her disease have reduced. Although according to the American College of Rheumatology, there is a 50% recurrence within 2 years, but Rebecca’s doctors are hoping to see her outgrow it. While Michaeli needs oral surgery for her crossbite, she can’t have it due to the fear of her jaw becoming a hotspot for CRMO.

“My time in the hospital was really interesting. I still remember I met so many different people,” Michaeli said. “I think that’s what impacted me the most, not the illness, but just the experience.”

Wagner, although now diagnosed and treated, has to take hydrocortisone daily and wear a medical alert bracelet in case she were to go into crisis.

“When I go to college, I have to make sure that I’m near a hospital that is willing and able to work with me on this,” Wagner said. “I can never live by myself because there always has to be someone there who knows what’s going on. I can never travel alone, either.”

If Michaeli and Wagner had gone undiagnosed, both described a similarly dire possible outcome.

“The really scary part is the unknown, because you have no idea what to expect,” Michaeli said.

“I think the best thing we can do right now is to inform people about it, because most people don’t know what it is or they haven’t heard of it at all,” Sophia said, “If there is someone with Addison’s, it can go downhill very fast if they get misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all.”