Staff Editorial: Managing Microaggressions

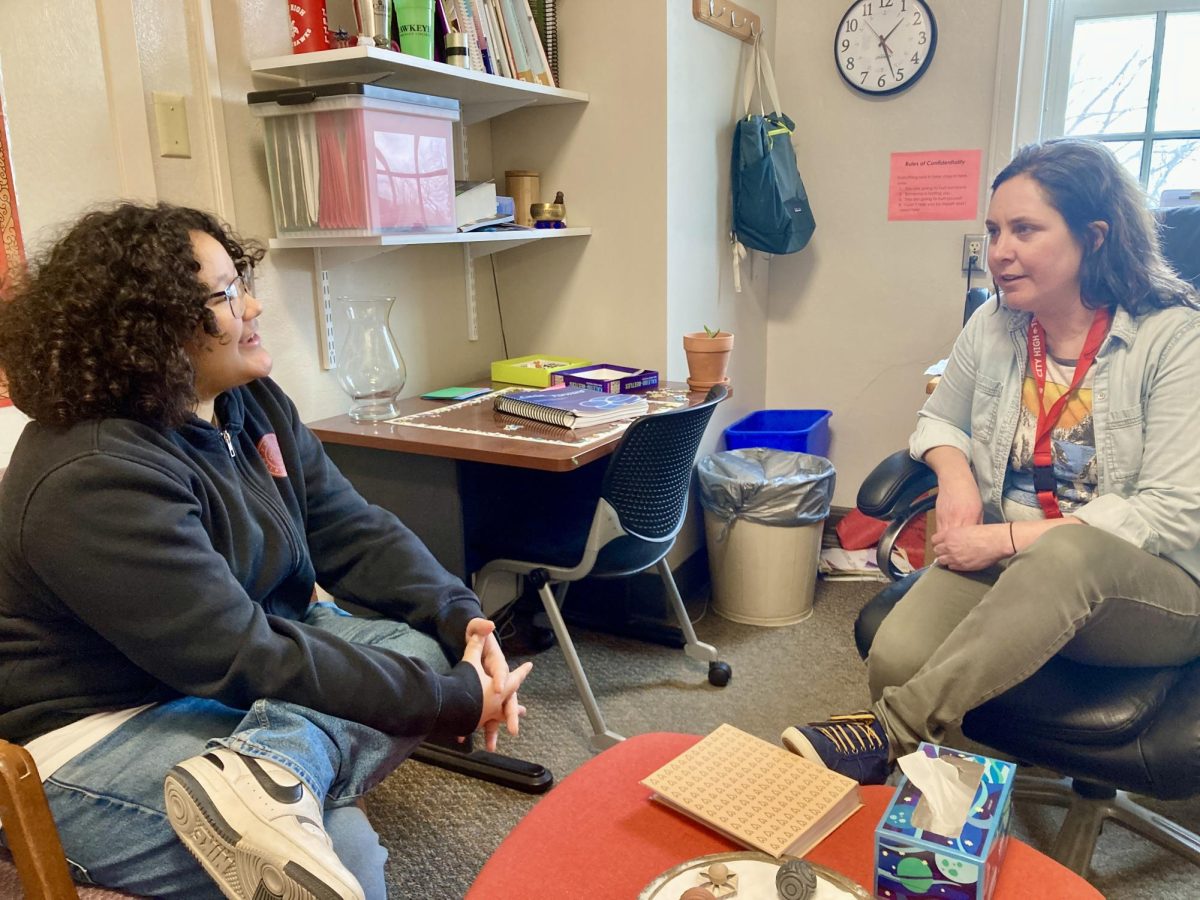

Art by Haileigh Steffen. Being a teacher is a difficult job, but that job is made even more difficult when female teachers have to deal with microaggressions in the classroom.

December 31, 2019

“‘She’s feisty. I like them when they’re feisty,’” City High English teacher Jennifer Brinkmeyer heard as she walked away from a student she was supervising for testing after she asked him to be on task. Along with experiencing other microaggressions, Brinkmeyer is used to having male students who would whistle her over in order to gain her attention.

It is undeniable that sexism is pervasive in the education system. However, the sexist microaggressions that occur in the classroom towards women have been far too overlooked. The nature of microaggressions is in the word itself. Because these sexist remarks are so seemingly small, we tend to excuse them or miss them.

“I hadn’t been really aware of what it was that I had experienced and that I had witnessed others experiencing,” Lauren Darby, the City High IJAG teacher, said in reference to sexist microaggressions in the classroom.

These microaggressions are not only hurtful, but harmful to a woman’s authority in the classroom.

“No matter how credentialed you are, no matter how intelligent you are, no matter how experienced you are, there’s still going to be a guy who can take you down with a single comment. And that is rough,” Darby said.

Noticing and acknowledging microaggressions, however, is far different than being able to call them out and stop them from happening. One of the barriers that female teachers face when calling out microaggressions is the idea that they can’t be perceived as “too emotional” or “too sensitive.”

“I try not to let my emotions get the best of me in a way that will make it so people won’t be able to listen to me. I think that’s just part of being a female teacher,” Brinkmeyer said.

Not only must female teachers be weary of the emotions they display in the classroom, but also the fact that they react to the microaggressions themselves.

“Sometimes I just want to scream at people, ‘No, you’re wrong. Stop using the phrase “politically correct.” That is a tool of oppression.’ But it’s not gonna get me very far,” Darby said. “I’m still going to be the ‘PC police’ or I’m still going to be a ‘social justice warrior,’ and for some reason that’s become a negative thing. But it’s just one of those many ways that people in power have manipulated the conversation to their own terms.”

Because of the stigma of female emotions, female teachers have to be aware of the way they let their students see how microaggressions affect them.

“Obviously [microaggressions] affect me, but in the sense that they remind me that the work is not done. But I don’t allow them to change who I am, or cause me to dim what I’m here to accomplish,” Brinkmeyer said. “I’m not going to be bullied by microaggressions into submission. But I’m aware that that just means that teaching is important. Women leading is important.”

In addition to the way female teachers are perceived when combating microaggressions, they must also navigate how to properly deal with students’ microaggressions.

“There’s the question of ‘Am I providing the example I want to provide for my students?’ But in those moments, there’s also a lot more I play of, you know, is now the time to get into a power struggle? Is now the time to engage with that student, or do you wait until after the class in order to de-escalate the situation or to rebuild trust?” Darby said.

For both Brinkmeyer and Darby, they try to keep their female students in mind when speaking out against classroom microaggressions.

“I also try to watch out for microaggressions among students. I’m very mindful of when there’s a small group with only one female student, and the male students make that one female student the recorder,” Brinkmeyer said. “I talk about how that works as kind of the assumed labor…that is something that female students are expected to do.”

Both Brinkmeyer and Darby pay attention to their own experiences and those around them when noticing microaggressions.

“I try to interrupt where possible because I have a daughter. I’m very aware that what I let slide—I don’t want to teach her that that’s what she should let slide and also the other students in my classroom when I have female students who hear these things,” Brinkmeyer said. “I grew up not really learning what to do about it; you just kind of ignored it.”

Too often female students are invalidated by their male peers for being intelligent, often called “teacher’s pets” and “smart-alecks.”

“I knew as a high-schooler I had those experiences plenty of times where I was made fun of by boys in my class for participating or knowing answers. And it took one of my male teachers standing up for me to shut them down and to make me feel like I belonged in that room,” Darby said. “I felt like I couldn’t provide that same service to my female students because the boys were still writing me off, and saying,’ Oh, it’s just because you’re PC or feminist or whatever,’ and it just felt like nothing I could say would change their minds and that they needed to hear it from one of their own, which is very frustrating.”

For female teachers, it’s not just about their experiences as teachers, but also making sure their students don’t have to go through the same things.

“I want to show my female students that this is not tolerable, and that goes for any marginalized group in a classroom,” Darby said. “You know, if something comes up, I want to make it clear [that] this is what we value in this room and this is what is okay and this is what is absolutely not okay. But I also know that someone who’s backed into a corner or shamed publicly is more likely to double down.”

It is everybody’s job to call out this blatant sexism.

“The thing has been interrupt, interrupt, interrupt when you see it. It happens so often that people don’t even realize it. Just drawing attention to it, I think, is, is the first step,” Brinkmeyer said. “I think it’s very different to be a teenage female now than it was when even 20 years ago or when I was in school. I think there’s a lot of forward momentum happening, a lot of forward progress, but we’re just going to have to keep interrupting, and just keep taking up space.”

But it can’t be only female teachers speaking out against these transgressions. It won’t stop until male teachers and peers alike are noticing and preventing this behavior.

“Male teachers need to be equally aware of those standard gender roles in the classroom. Are you always having a female student pass back the papers and be[ing] teacher’s little helper and recording the notes? People can watch out for male students…interrupting female teachers or male students interrupting female students,”Brinkmeyer said.

Recently, Brinkmeyer had a student tell other male students who were talking during a female student’s speech to be quiet.

“It was such a cool moment for me. Here’s this boy realizing her voice matters in this room, and everyone else needs to shut up. It was super cool,” Brinkmeyer said.