Krepcha: The Better Beignet

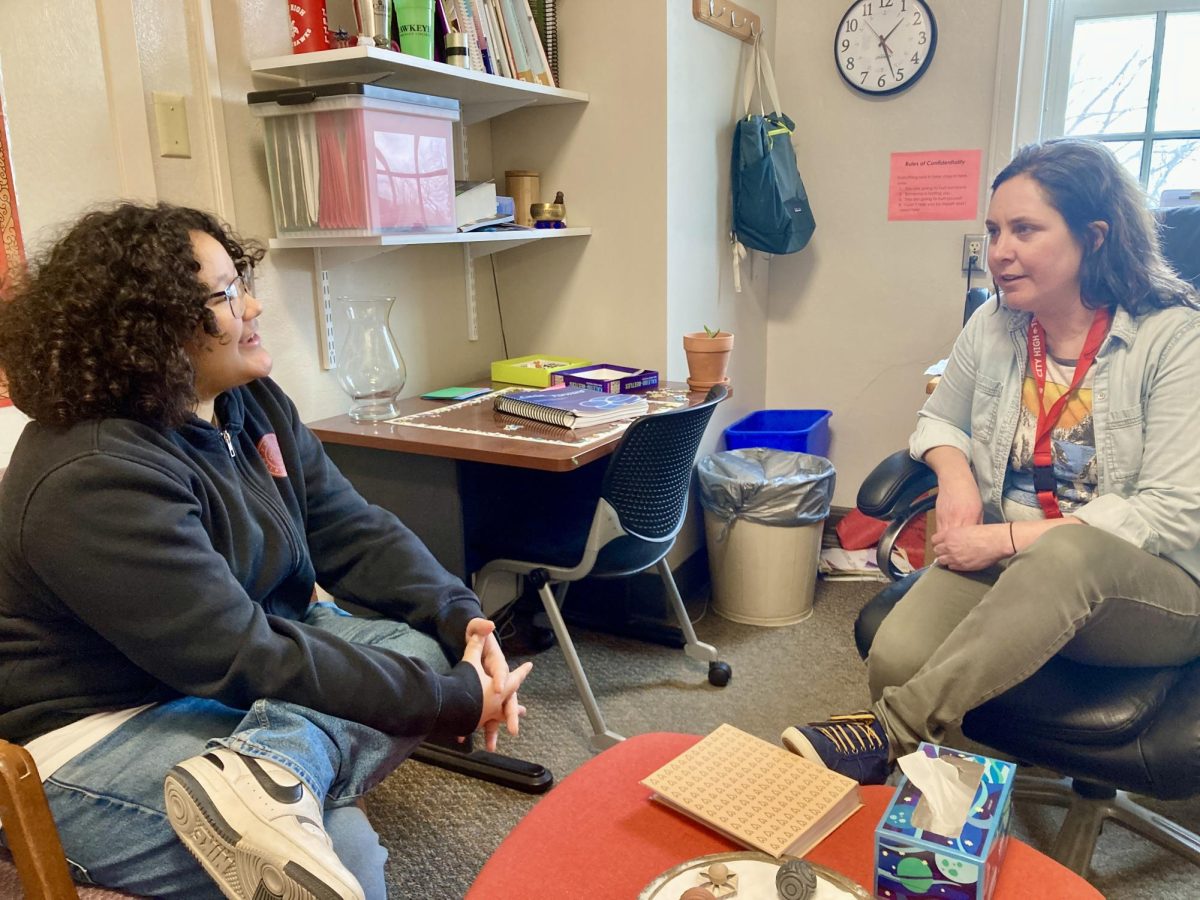

Krepcha dusted with powdered sugar.

February 4, 2020

In my early memories, Sunday mornings are filled with light, laughter, and powdered, fluffy pastries. My dad would get up at six in the morning, tie an apron around his waist, and prepare the dough, getting elbows-deep in flour before his morning coffee. We would leave it for an hour while we went to church. We’d get back, I would race up to my room to change out of my stiff church clothes, and then tumble back downstairs with my brothers to line up beside the stove with a plate, like we were in a hot soup line. My dad would delicately take a piece of the dough from where it fried in a big pan and place it on a large plate covered in paper towels, then dust the pieces with powdered sugar. If they were too hot to touch, we would burn the tips of our fingers to get the coveted pastries onto our plates and into our mouths.

Krepcha is essentially a less-sweet beignet. For the dough my dad uses flour, yeast, and water with a little salt. The chewy dough keeps together quite well and is almost elastic, not crumbling easily. The powdered sugar is what makes it so delectable. Without it, krepcha tastes like bland, dense bread. It is best served hot and fresh, as I have learned, since heating it up in the microwave tends to melt the powdered sugar and leave the krepcha unevenly warm.

Since “krepcha” is not recognizable as a food by any Google search results, searching for beignets reveals a surprising origin story: beignets, the popular food in New Orleans brought by French settlers, originated in Ancient Rome. There are many versions of the fried-dough food; apparently people have had a soft spot for fried dough for a very long time. Versions of beignets stretch across Europe, Africa, and Asia in forms such as berliner pfannkuchen (Austria, Germany, Switzerland), boortsog (Central Asia), gogoşi (Romania), paczki (Poland), buñuelos (Spain), horse-ear pastries or 牛脷酥, 马耳 (China), and mandazi (East Africa). A lot of the fried dough pastries also have some kind of filling, like jam or chocolate, though krepcha and beignets don’t have a gooey center.

The way my dad makes krepcha is different from beignets for a few reasons. There’s little sugar in the dough, for one, which is why we dust or dip it in sugar when we eat it. My dad learned the recipe from his babushka and it has been passed down orally for generations. Babki, my dad’s grandma, made it differently than he does, but the main idea is the same. Babki let the dough rise, made using flour, yeast, milk, sugar, water, salt, and my dad suspects eggs. Then she pulled a chunk of the dough up out of the mass and stretched it out like taffy before taking a knife and gently sawing through the dangling rope of dough. She was left with a mound that she shaped with her hands before frying. Instead of sprinkling powdered sugar on top, Babki used granulated sugar. They piled it in little heaps on their plates and dipped the fried dough, coating the pieces with a thin grainy film.

When my dad learned other methods of cooking and experimented in the kitchen, he started combining recipes with krepcha. He made a few adjustments to what Babki taught him. For example, he doesn’t make krepcha with eggs, and instead of holding the dough in the air to cut it, he rolls it out on a floured cutting board and slices it into pieces, which he said makes it easier to portion out and slap into the pan. He mentioned that the dough “rises fast,” though if that’s in comparison to beignets I can’t tell the difference. They both take about an hour to rise, while bread takes quite a bit longer. The finished product is chewy, warm, sweet, and I could eat about 12 at once. I find that krepcha are great with milk or orange juice.

Ingredients:

Milk (1 cup)

Water (½ cup)

White sugar (1 tbsp)

Yeast (1 packet)

Flour (4 cups)

Butter (½ stick)

Salt (1 tsp)

Powdered sugar (for topping or dipping)

Directions:

Take 1 cup milk plus about ½ cup water

Heat on the stove so it is warm but you’re able to put your finger in without burning

Add tablespoon sugar and stir in packet of yeast

Let yeast bubble (5-10 min)

In a bowl, combine 4 cups flour, ½ stick softened butter, and 1 teaspoon salt

Pour yeast/milk into flour mixture and knead dough

Cover with Saran Wrap and put in warm oven, about 90 degrees — here he writes “(NOT HOT)”

Let rise about an hour.

Punch it down and roll out on floured cutting board

Cut into twenty squarish pieces

Cover with Saran Wrap and let rise 20 minutes

Fry in hot oil

Sprinkle with powdered sugar on paper towel

Enjoy!