Queer Stereotypes: The Harmful Impact

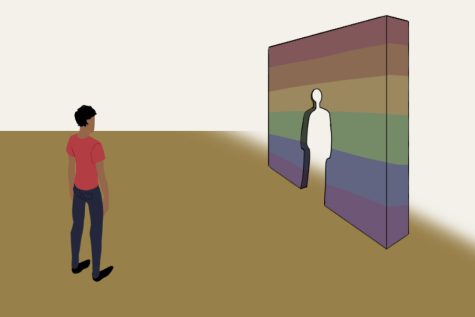

For queer students, the increasing use of stereotypes can negatively impact their day-to-day interactions

The are many queer students who feel like the stereotypes about them are not always true.

April 13, 2022

Strolling through the hallway, Braeden Marker ‘23 can be spotted sporting long hair and earrings. In men, both of these things can be associated with being queer in some way. Marker says he has experienced being associated with queer stereotypes just because of the way he chooses to express himself even though he identifies as straight.

“I don’t really care a whole lot. However, it does make me kind of sad, because I do see the harm in those stereotypes, and how they can restrict people from behaving how they want to behave naturally,” Marker said. “Even though none of those things actually have anything to do with sexuality, it often gets associated.”

Marker thinks that regardless of the type of stereotype, almost all stereotypes that are out there do not have a positive impact on the people who they are about.

“Honestly, I feel like generalizations really just end up as restrictions on people in every single application, even if those restrictions aren’t super negative,” Marker said.

Stereotypes about queer people extend far wider than just earrings though, according to Maya Bennett ‘23. She sees numerous stereotypes related to each label which range from how people dress to aspects of their personalities.

“There are a lot of stereotypes that circulate around the internet that fit specific labels and I think that each label has a stereotype attached to it,” Bennett said. “[For example] more masculine clothing for gay women [and] more feminine for gay men.”

Even though the number of adults in the United States who identify as LGBTQ+ has risen to 7.1% up from 5.6% in 2020 according to a Gallup poll, the use of generalizations about queer people still persists. Reyna Roach ‘24 has heard many negative stereotypes about trans and queer people in general.

“[There’s] a stereotype like trans people have to dress in the way that says people will perceive their gender which really sucks when you don’t do that,” Roach said. “So many people view queerness as like an illness, just like straight up, and they view queer people as trying to infect their children and encroach on their spaces.”

Regardless of the kind of stereotype, they almost always have a harmful impact on the people that they are about, according to Kenji Radley ‘25.

“I’ve had lots of sort of friends tell me I should be doing this or that because I’m gay or something which [can] impact relationships a lot,” Radley said. “I think that it can affect people’s mental health and the way they feel like they need to be to get validation from others.”

Similar to Radley, Bennett agrees that the use of stereotypes can have a harmful effect on people in the queer community.

“I think [stereotypes] can make you feel kind of trapped within a certain way of expressing yourself for identifying. It’s not always true, and when it’s not true, it doesn’t feel good,” Bennett said.

In the same way that many stereotypes are based on some type of truth, Roach believes that queer stereotypes often are based on something that is commonly done by some queer people. They think that queer people will often play into stereotypes because they want to be identified in the queer community.

“Just because people will negatively attribute things to [queer stereotypes], it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do them. Sometimes you feel like you have to [fit into stereotypes] because otherwise, people will not accept you for who you are,” Roach said. “It also [has to do with] identity. Being able to identify each other is good because then we can find people more easily that we are safe around.”

Social pressures are another reason why people often fit into stereotypes. Marker thinks people often believe that if they don’t act in the way that stereotypes tell them to, they won’t be thought of as a part of their own community, or their sexuality will be questioned.

“Even perceived social pressures can be enough to push you into trying to fit a certain category,” Marker said. “If it feels like this is the way you’re supposed to be because this is what you see, then you’re going to try and act that way.”

Roach believes that even if queer people do happen to fit into the stereotypes about them, that does not mean it is their fault for perpetuating the use of the stereotypes.

“I think that’s a straight people narrative. Like, oh, the reason that you’re getting harassed is because you look a certain way,” Roach said. “When you’re outside of the queer community, you can use the stereotypes as an identifier for people to harm or to put impressions on people that you don’t know.”

Bennett says that part of the reason that we rely on stereotypes so often to determine sexuality is because even today, there is a perceived fear of asking people what their sexuality is.

“Homophobia is real, so you don’t want to ask and then be made fun of in some cases, or you don’t want to ask and then make the other person think that you [are interested in] them,” Bennett said.

However, Bennett and Roach believe that relying on stereotypes is what often leads to the idea of the ‘gaydar’ which can be unreliable. The ‘gaydar’ is the idea of the ability to determine sexual orientation through subtle clues. According to Psychologist Today, the ‘gaydar’ is just a form of social intuition which can be accurate but is far from foolproof.

“I think it’s always best to ask the person and learn how they identify and express themselves instead of making assumptions about people,” Bennett said. “You have your right to ask and get to know the person, but I think that it’s never your place to assume or to spread something [about] other people because it might not be true.”

Marker thinks that the fear of breaking stereotypes can sometimes become something that both straight and queer people are afraid to confront.

“These ideas about how you’re supposed to behave, and more specifically how you’re supposed to interact with other people, especially people of the perceived opposite sex, can absolutely change how gay men act, especially because they don’t feel the need to fit toxic masculine stereotypes,” Marker said. “A lot of it ties into toxic masculinity. For example, a lot of straight guys are afraid to grow their hair and things like that because it’s so ingrained to them that this is a gay thing.”

Recently, Roach has seen more nonqueer people do things that are usually seen as queer. Even though it is usually just meant as a joke, they think that it can still be viewed as hurtful to people in the queer community.

“Sometimes when straight guys kiss other guys, they’re using it as a joke,” Roach said. “[They are implying], ‘I would never actually be gay. So I’m totally safe kissing people and no one would think I’m gay, cuz that’s just outrageous. That would never be me.’ That is homophobia.”

The biggest thing that can be done to help eliminate the harmful effects of queer stereotypes, according to Marker, is to encourage all people to feel comfortable in expressing themselves however they want to.

“Having an honest conversation with yourself and thinking about [why] I am acting this way? It sounds extremely cliche to say, oh, just be yourself, but be fully aware of why you’re acting the way you are because if you’re not, you’re likely going to fall into many stereotypes and perpetuate the issue,” Marker said.

Bennett thinks that it is important to create a culture where jokes about queer people that could be offensive are unacceptable. She believes that means holding each other accountable for the things that you say, especially among friends.

“I think recognizing the jokes that you’re making and the assumptions that you’re making, and reminding your friends or not making it into a joke if any stereotypes or assumptions about people and their sexuality come up,” Bennett said.