Biracial teens at City High not only question their identity from an outsider’s point of view but often ask those same questions themselves. With being mixed comes a unique sense of identity and perception from others. Being forced into a box is a common experience for biracial teens.

“I consider myself biracial. I’m mixed. I’m black and white,” Cameron Echols ‘26 said. “Sometimes [I have trouble fitting in] just because some people will say ‘you’re barely even black’ or ‘you’re barely white.’ That makes me feel like I don’t fit in with them. I know what I am, so it shouldn’t make me feel like that.”

The students around teens have an impact on how biracial teens view their own identity. Being mistaken for almost everything in the book brings in uncertainty about their own self.

“I feel like it depends on who I’m around, who I’m talking to at the moment. There’s people who will say things that make me feel disconnected to my culture,” Echols said.

However, every mixed person’s relationship to their cultural identity varies from teen to teen.

“My mom is a very cultural person from Laos. She brought a lot of that culture with her and so she’ll take me and my brother to the temple and [we’ll] practice Buddhism with her. I’ve been very connected with my mom’s side. That’s what I grew up on,” Poi Borchardt ‘26 said.

When it comes to extended family with two different cultures, being with a certain side may be extremely different.

“I think it’s weird with my dad’s side. I just feel weird going over there because it’s strange being the only people of color there. Then going to my mom’s side, it’s weird being the only one who’s mixed with white there. They make assumptions,” Borchardt said.

Depending on each mixed person, their connection to their culture is always different. Whether that be feeling like an outsider, or being completely immersed in the culture from a young age.

“Yes, [I am connected to my culture]. Growing up, my family has always loved doing things from our culture and making sure that me and my brother know all about it,” Layla Lovan ‘25 said.

Although a mixed teen may feel confident when it comes to their culture, that same confidence isn’t always there when it comes to their mixed identity.

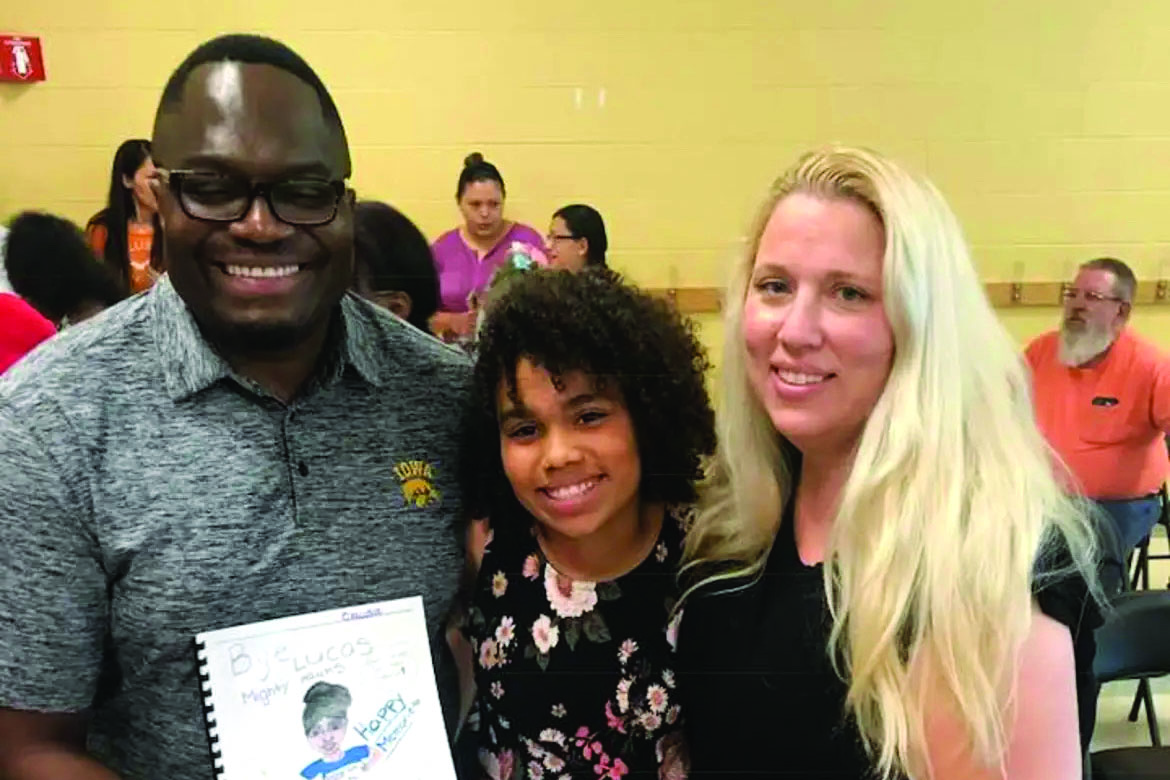

“I don’t know if I’ve ever been ashamed of it, but I feel like sometimes I’ve been fearful of it, just because sometimes when people find out you’re mixed, they try to make you choose a side or choose one culture over the other even though you have both. It’s hard to find a place when you’re mixed,” Claudia Lusala ‘24 said.

Growing up with that sense of not belonging and being out of place from a young age furthers the notion that as a mixed kid, you have to pick a side. According to Lusala, no matter what side you choose, you will be penalized.

“In middle school, people made you pick a side. You feel detached from your culture, and with being an African, it’s kind of hard to embrace Americanized Black culture. It’s very hard to step into that because you kind of have a very different view. African culture is very different from Black culture in America,” Lusala said.

To connect with Lusala’s father’s side, learning Congolese was a must to be completely engaged with that culture.

“I feel like it’s really hard to be fully involved in that culture when you really just can’t understand what’s going on fully. It’s also a translation barrier. You can translate some of these things into English, but they don’t have the same emotion behind them and the same feeling,” Lusala said.

When faced with two distinct sides of a person, it is important to acknowledge and learn from both sides.

“I feel like my mom really embraced my dad’s culture. So I feel like I definitely got way more of that side’s culture. I still had my mom’s family and everything and they brought that culture in, but I feel like mainly it was Congolese culture that was fronting my whole childhood,” Lusala ‘24 said.

Although many mixed teens are pressured into picking a side, it still doesn’t affect the fact that no matter what, they are mixed.

“I’m half Congolese, and then I’m half white. So when I tell people my race, I just tell them I’m Congolese and white. It’s not like I can really consider myself as one thing since I am both,” Lusala said.

While the sense of identity is a major part of mixed teen’s problems, the racism they face also adds onto the insecurity.

“I’m not ashamed [of being mixed], but I’m not open about it. I was scared for some reason. I don’t know why. I think it’s just because of past experiences with racism,” Lovan said.

Borchardt explained that living in Iowa means that most people around her don’t look like her or share her same experiences.

“It all comes down to the beauty standard. Asian cultures definitely have a harsh beauty standard. I don’t know if other people would know how difficult it can be because the Asian population around this area is very low,” Borchardt said. “So it’s like, ‘oh, I wish I was as pretty as this girl who is pale with blue eyes and has natural blonde hair. I wish my hair was lighter. I wish my eyes were lighter.’ I wasn’t necessarily ashamed [of being mixed], but I wished I looked more like them so I could fit in.”

The racism aspect of being mixed further outcasts teens due to both sides experiencing race and racism differently.

“When it comes to other people who are fully Asian I don’t feel out of place. But people who are fully white, kind of because they just don’t understand. It’s like they don’t understand what it’s like to grow up with having an immigrant as one of your parents and just the disconnect you can feel,” Borchardt said.

Of course, being mixed doesn’t just have downsides.

“It definitely was interesting learning that this isn’t what everyone knows. Not everyone does this or celebrates these things, especially with having white friends that don’t know anything about other cultures. It makes me really grateful for the things that I know in my culture,” Lovan said.

Being mixed also means easier access to different cultures, further exposing people to different lifestyles and learning more.

“I feel like one of the biggest benefits is having different cultures, even though at some points it’s hard, is that you’re definitely learning a lot more with two cultures at hand. I’ve learned a lot of knowledge from my dad about being an immigrant and moving to America. Also I have a lot of knowledge from my mom,” Lusala said.

Some mixed teens find being mixed to be an opportunity to engage with other cultures, while others may see it as more of an obstacle. Others are completely indifferent towards that part of their identity.

“Because living in Iowa City is pretty diverse and there’s a lot of people from everywhere, I don’t feel like [being mixed has] hurt me in any way. But going to my mom’s side who lives in rural Iowa is a little scary,” Echols said.

Borchardt explains that the downsides of being mixed, however, also include not having your experiences with racism taken as severely.

“I’ve experienced racism but it’s not taken as seriously because some people consider me white passing. So it’s like, ‘oh, did that really happen to you? You’ll be fine. How are people racist to you? You look white,’” Borchardt said.

Echols explains that another setback of being biracial is how other people view you.

“I feel like there’s been times where I’ve been told you don’t act that way. ‘You don’t act black or you don’t act white.’ I feel like you can’t really act a race or ethnicity. I don’t appreciate it when people say that for sure,” Echols said.

With so many pros and cons of being mixed, the people that surround teens are a major factor in how they will see being mixed as.

“It’s definitely weird when it comes to the social aspect. Having friends who aren’t mixed, especially living in a predominantly white state and going to a predominantly white school, especially with the Asian population so low, it’s hard [to find] multiple people who can experience the same things as you,” Borchardt said.

Despite all of this, being mixed is not something that anyone is able to change. If someone is mixed, they still have to live with it. Regardless of the hardships that come with being mixed or biracial, it is completely possible to find confidence and security with your identity.

“People around you just assume you have to pick one of the two sides. But I feel like once you embrace that you don’t have to pick two sides, you can really accept yourself,” Lusala said.