Sebastian Sauder ‘24 was ready to go to bed when the glow of his smartphone’s screen distracted him. Just a click away were all of his grades, various to-do lists, his bank account, and his entire calendar–not to mention the whole internet, TikTok, Instagram, and Tumblr.

In 6th grade, Sauder was the first member of his family to acquire a smartphone. Now, as a senior, his phone has been fully integrated into his life in ways that are sometimes disruptive.

“[My phone’s] ability to make work so present, when it’s time to sleep, is always difficult for me, because I end up doing my schoolwork and other work and life organization at night,” Sauder said.

Sauder’s sleep schedule is inconsistent; he sleeps approximately nine hours during “good weeks” and five hours during “bad weeks.” He uses a number of sleep aids on his phone such as music and timers. Sauder, who has struggled his whole life with insomnia, chooses not to look at the number of hours he spends on his phone per day.

“I’m kind of addicted to my phone, but I’m self-aware about it,” he said.

Sauder is a strong academic student and has taken courses at the University of Iowa. Nonetheless, he often struggles to focus in school because he doesn’t feel well-slept.

“When I’m this tired, I’m not trying to learn. I’m just trying to get through the day so that I can go home and take a nap,” Sauder said at nine AM.

Sauder uses his phone in lieu of an alarm clock and often struggles to wake up in the morning.

“I can’t name a single day that I’ve felt fully awake the whole time,” Sauder said.

Sebastian Sauder is by no means the only student at City afflicted by the ever-luring effects of a glowing phone. In fact, many students report getting even worse sleep. A survey sent out to all students at City High yielded the following results: Of the 132 respondents, only 39 students (29.5%) regularly get the advised eight or more hours of sleep each night (per CDC recommendations). The majority, 70.5%, get fewer than eight hours of sleep per night.

“Sleep deprivation is one of the primary barriers to academic success,” Ali Borger-Germann, English Language Arts teacher, said.

According to the National Institute of Health, the reason that electronic devices are so detrimental for sleep is primarily because the blue light exuded from screens, which has the effect of reducing humans’ melatonin, a sleep hormone. This causes smart phone users to stay up later at night. And the effects of the usage of devices extend well beyond waking hours: they have also been shown to reduce rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the most important and restorative period of the sleep cycle.

Megan Stucky-Swanson, City’s Orchestra Director, cited exorbitant phone usage as a serious issue in the lives of teenagers and adults alike.

“It’s a distraction that we’re all used to at this point. There are lots of different types of social media. It’s how you read articles and sometimes how you read books. And that strain on your eyes [is harmful], especially when you’re trying to wind down before bed,” Stucky said.

Stucky encourages those in her first period class, Symphony Orchestra, to arrive early so that they are able to get their instruments unpacked and ready to rehearse. Despite this, students occasionally arrive late.

“It’s hard, sometimes, to get the early morning classes awake and engaged and their brains ready to go if they’re not feeling refreshed,” Stucky said. “Students clearly don’t get enough sleep. I think that students are on their phones too much, especially right before they go to sleep, which is one of the causes of insomnia.”

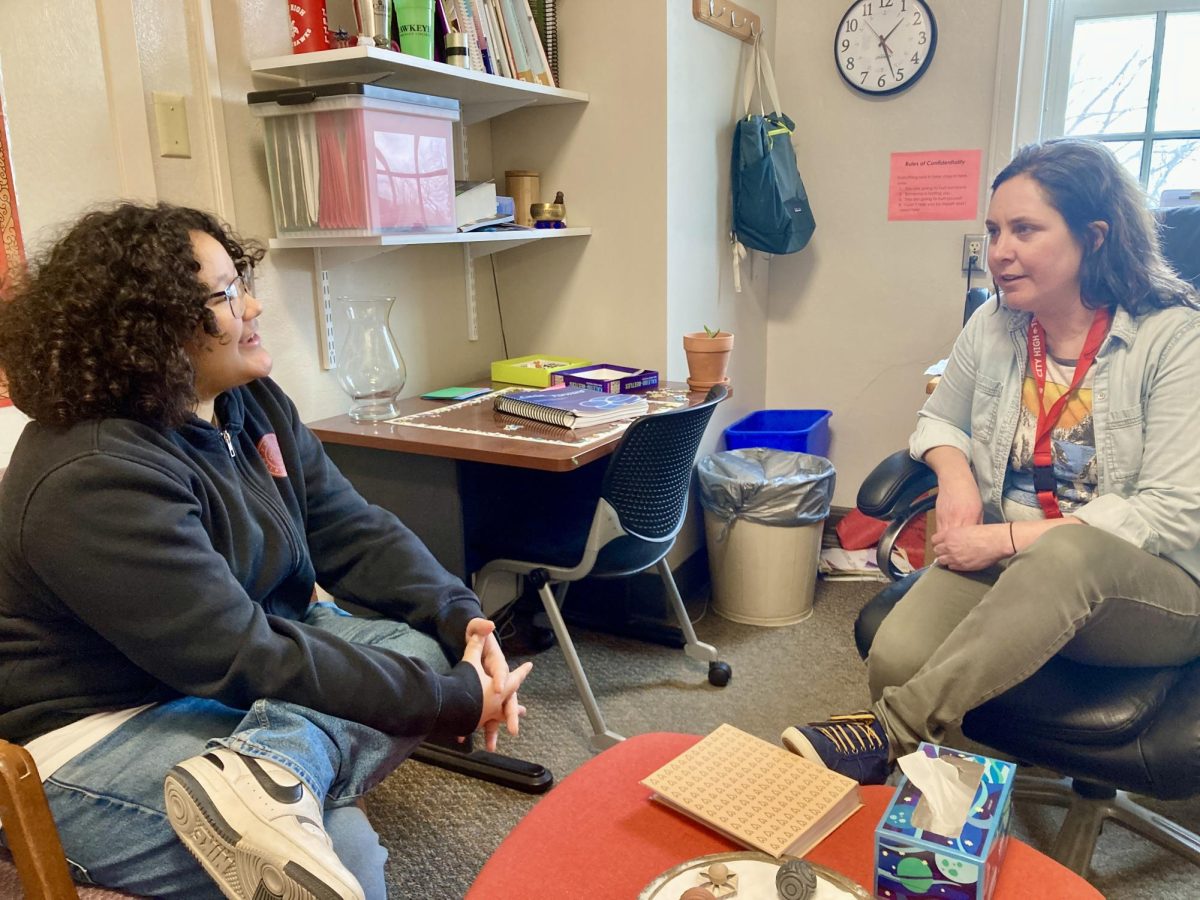

Guidance counselor Mary Peterson said that many of her students appear to be underslept during the day.

“Often, when I talk to students, and I ask what time they go to bed, they smile. And then they’re like, ‘Uh. . . two. One.’ And I’m like, ‘Agh, what are you doing?’ And they’re like, ‘Well, I was on my phone.’”

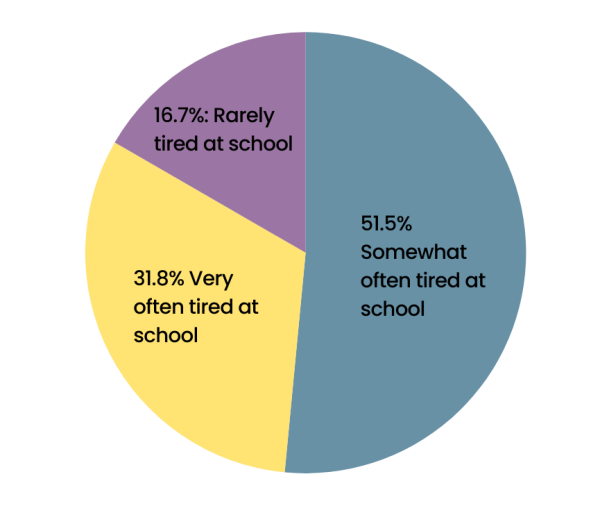

In the survey of City High students, 31.8% reported being “very often tired” at school, while 51.5% reported feeling tired “somewhat often” and the last group, 16.7%, “rarely tired.” Peterson believes that this lack of sleep greatly affects students’ daily lives.

“If you don’t get enough sleep, you’re too tired, and you can’t focus, you can’t concentrate. You don’t want to be engaging in learning,” Peterson said.

Peterson believes that students aren’t learning to build healthy habits with technology, and that this negatively affects their learning.

“There are times when the phone or the computer or the TV needs to be away,” Peterson said. “You shouldn’t do anything else in your bed except for sleep.”

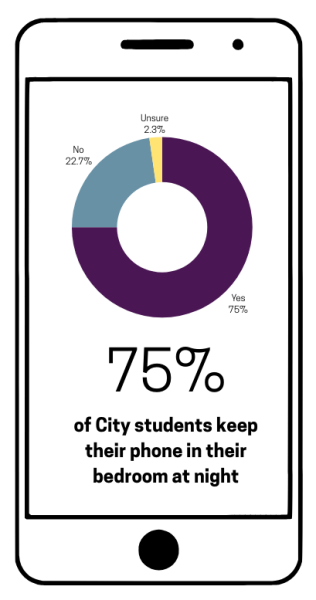

According to the survey, 75% keep their phone in their bedroom at night.

“I’m always curious to see students’ screen time,” Peterson said. “A coupe of years ago, I had a student show me theirs, which was already eight or nine hours, but it was only noon! So most of that usage was probably at night–which is totally crazy!”

When she was a freshman, Noe Richman ‘25 fell asleep in her science class after staying awake for five consecutive nights. This past year, her circadian schedule has improved slightly: she has been getting approximately four hours of sleep per night. She often spends the early hours of the morning working on homework.

“I’m so groggy in the morning and I just dread every day, so it’s harder to get out of bed,” Richman said. “I get less sleep than I would otherwise because I need time to rejuvenate in the morning, because I’m so exhausted.”

Some students are figuring out how to more effectively regulate their sleep. As a sophomore, Olive Jackson ‘25 struggled maintain a consistent sleep schedule, and would often go to bed past midnight, only to wake up in the middle of the night. At the beginning of her junior year, Jackson decided to regain control over her schedule.

“[I realized that] it’s all about what you do before you go to sleep,” Jackson said. “Like, not doing things. I try to not eat, exercise, work, or look at screens, [starting at specific times] in the afternoon and evening.”

After experimenting with several strategies and reflecting on whether they worked for her, Jackson’s schedule improved significantly. This year she has been going to bed at nine PM and waking up at five AM every single day.

“Winding down and going to bed at the same time every day has helped me. When I don’t do the routine, I feel worse, and I don’t feel well-rested,” Jackson said.

Jackson keeps her phone in her room at night and uses it as an alarm clock, but she doesn’t look at it for an hour before bed. She reads paper books before going to sleep.

“Blue light dries out my eyes, and it doesn’t make me tired the way that reading a book does,” Jackson said.

The increase in technological ubiquity in the U.S. was significantly accelerated by the pandemic, according to the National Health Institute. During this time, sudden quarantines and restricted access to normal life led to an unprecedented shift towards electronics. Many of the systems encouraging the usage of devices over more traditional methods have remained in place.

During the pandemic, Adrian Bostian ‘23, a former City High student, found himself spending hours scrolling TikTok, to the detriment of other aspects of his life, including his sleep schedule. He decided to delete the app.

“For me, [TikTok] was a really insidious addiction,” Bostian said. “I’ve observed so many people, myself included, naturally gravitate towards that short-form content. You just need it to be faster, you need it to be more stimulating.”

Bostian has observed the detrimental effects of extreme phone usage on his peers, and has tried to be mindful of his own.

“When I’ve spent too much time on my phone, I feel an increased sensation of apathy,” Bostian said. “Because I’ve spent however many hours of my day doing an activity that is manufactured. It’s manufactured to be the most stimulating thing you could imagine, and the most infinite form of stimulation. And so unfortunately, other activities that you can do in a day don’t always rival the instant reward of the phone. . .”

According to the National Library of Medicine, use of devices is directly correlated with a decrease in mental health. Symptoms range from anxiety to clinical depression. These symptoms often cause or exacerbate insomnia.

Bostian tries to avoid spending extended periods of time on his phone. Bostian tries to avoid spending extended periods of time on his phone. He described the experience of sitting in class during breaks or dull moments and noticing that all the other students were on their phones. He finds this phenomenon to be “dystopian.”

“[It seems like] everybody is content to endlessly consume media,” Bostian said. “I think there is more of a general disinterest for the type of studying learning that you do in school. And that’s really sad because I think being educated and learning is extremely important, and that the media takes away from that.”

In the student survey, only 25.4% of students felt that electronics were the main cause of their sleep dysregulation. The largest category of students, 40%, cited homework as the main issue.

Orchestra Director Stucky believes that members of Generation Z students feel more pressured than previous generations to take on a heavy workload of rigorous classes and extracurricular activities, such as sports and clubs. The combination of schoolwork and activities often require significant time commitment.

“When you have all of that in a mixing pot, it doesn’t lend itself well to students feeling rested and awake,” Stucky said. “Sometimes, the only free time you have all day is that hour before you go to bed, and sometimes what you want to do is watch TV or scroll some Facebook.”

The long-term effects of phone usage on teenagers have yet to be fully documented.

“I think [learning to balance phone usage] is something that today’s teenagers are going to struggle with for the rest of their lives,” Stucky said.