A mile and a half away from City High is the University of Iowa campus, a Tier-1 public research university and one of three major universities in Iowa. Despite this, Kenji Radley ‘25 has still had trouble with college applications.

“I can’t stay in Iowa City because there’s no meteorology program here,” Radley said. However, he hasn’t let state boundaries stop him from reaching his dreams of becoming a meteorologist. Instead, Radley is applying to universities in Canada, the West Coast, and the Midwest (outside of Iowa).

The phenomenon of students leaving after graduating high school or college is known as brain drain. This pattern of educated citizens leaving a state can be detrimental to the state’s economy, growth, and standard of living. And for years, Iowa has been a leader in brain drain. In 2024, it was ranked 9th out of all 50 states in difficulty keeping students in state after graduating college.

“[If there were a meteorology program in Iowa City], I would probably stay. It would be a more sustainable option,” Radley said.

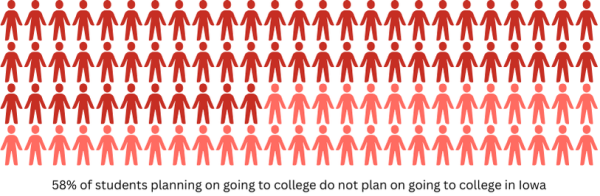

Most research on brain drain is focused on college graduation statistics, but for high schoolers, the effect is paralleled. According to a 2009 study on Michigan high schoolers from the University of Michigan, 58% of high schoolers saw brain drain as a big deal affecting their communities.

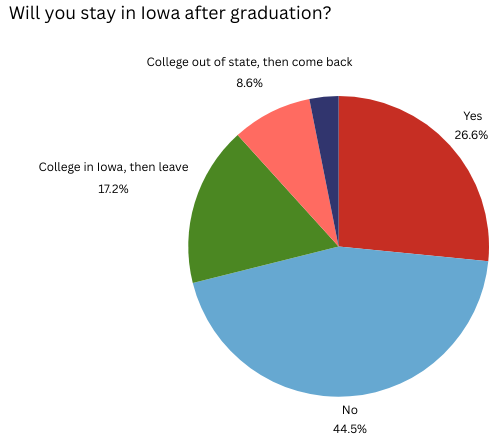

And most City High students don’t see a future for themselves in Iowa. According to a schoolwide survey with 128 respondents, a majority of students do not plan on staying in Iowa after graduating from City High. 44% indicated that they were not interested in staying in Iowa at all, 17.2% expressed interest in going to college in Iowa and then leaving the state, and 8.6% wanted to go to college out of state and then move back to Iowa. Only 26.6% of respondents wanted to stay in Iowa indefinitely.

“[Having lived] in Iowa my whole life, I want to move to another state and find new experiences,” Drew Brown ‘25 said.

“[Having lived] in Iowa my whole life, I want to move to another state and find new experiences,” Drew Brown ‘25 said.

Brown is not alone in wanting to develop new experiences. Nine respondents mentioned wanting to discover new places or experiences. Among the students who wanted to leave Iowa, there was an overarching theme of wanting to pave their own path and feeling stifled by the perceived mundanity of Iowa.

“I want to pursue an education outside of Iowa, because although [the University of Iowa] and Iowa State are good schools, I hope to go to a place with better topography, scenery and cleaner water. [I mostly want] a change of scenery,” said one student.

Iowa is broadly associated with the idea of “the middle of nowhere.” A majority of the state is rural farmland, and the few cities that pepper the landscape are small compared to cities in neighboring states, like Chicago in Illinois and Minneapolis in Minnesota. Iowa lacks a true metropolitan heartland that would draw in people from surrounding areas after graduation.

The Des Moines metropolitan area, home of Iowa’s largest city, has a population of 700,000. The St. Louis metropolitan area, in contrast, has about 2.79 million residents, and the Minneapolis area has around three million residents. To an Iowan wanting to live in a large city, the choice is clear–you can’t stay in Iowa.

College graduates in Iowa also leave at a higher rate than they stay. According to a recent analysis conducted by the South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce, Iowa ranks 9th among 50 states in net losses of college graduates. A study by The Washington Post says that college graduates tend to be drawn to states with large, vibrant cities like California, New York, and Illinois. However, Iowa’s cities lack the diversity and regional significance that more populous states have.

It’s not just that people want to get out of Iowa. 22% of total respondents (42% of students who indicated where they would want to move after college or high school) want to move to the East or West coast and 14% (27% of students who indicated) want to leave the country. This staggering statistic–69% of students uninterested in staying in the midwest compared to 30% who are–suggests that people want to leave not because they are not optimistic about job opportunities in Iowa, like many national studies and the Cedar Rapids Gazette suggest, but because they are unhappy with the local environment. Many students feel discouraged by the current political climate and state government. Some feel unsafe, and others feel out of place in the conservative state.

Axios Des Moines, a news source that covers both local and national news, attributed the loss of college graduates in Iowa to a lack of good jobs. Axios also reports that college graduates are moving to neighboring states like Minnesota and Illinois, but City High students are over twice as likely to want to move outside the midwest than to stay in the midwest but leave Iowa.

“Iowa is horrible for LGBTQ and any minorities, and I just wanna get outta here,” Ellie Medea-Kapp ‘26 said.

Iowa is currently controlled by an increasingly conservative legislature, governor, and legal system. In recent years, drastic changes to state law that directly affect students like banning books with “sexual acts,” requiring the Pledge of Allegience to be spoken every day, and outlawing gender neutral bathrooms have affected students and adults across the state. However, Iowa City presents a stark blue contrast to the overwhelmingly red majority of the state, so some left-wing students feel out of place and want to move somewhere where they will be more ideologically represented.

“There has been a strong change in the political climate of Iowa in the last couple of years towards really divisive policy that makes people less free,” State Representative Adam Zabner ‘17 said. “I hear from folks all the time who are not willing to live in a state where abortion is not legal or are thinking about having kids and they don’t want to go through that in a state where some of the restrictions on education have been passed.”

Coraline Etler ‘26 is one student who is considering leaving not just Iowa, but the country, due to her political beliefs.

“The majority of Iowa does not share my values,” she said. “[But] I love Iowa City. Since the [2024 General] Election, I’m wondering if I even want to stay in the U.S.”

Jillian Conlon ‘26 agrees.

“I just want to live somewhere where Kim Reynolds isn’t the governor and preferably somewhere that votes blue,” she said. “I would also love to see the world and live near water.”

Both Conlon and Etler’s responses demonstrate the overwhelming trend from the City High survey of wanting to explore new places and leaving the conservative state of Iowa behind. However, some students do find concerns when faced with future job prospects.

“Only one university in Iowa offers the program I’m interested in,” said Jethro Michaelson ‘27, who wants to go to California Polytechnic State University to study urban planning.

The only university in Iowa that offers an urban planning program is Iowa State, in Ames. The University of Iowa has a similar program called environmental planning, which focuses more on environmental issues, but Michaelson is more interested in people-related issues in urban planning like transportation equality. However, neither the Iowa or Iowa State program is very prestigious, which turns Michaelson away and forces him to look outside Iowa for a suitable course.

Not everyone wants to leave Iowa. For some, they can see themselves being happy and content in Iowa, provided that they have opportunities to grow and succeed.

“I think I’ll probably stay in Iowa,” Max Brown ‘26 said. “I like it here, my family’s here, and it’s nice.”

Adam Zabner ‘17, a City High graduate who is now a state representative in the Iowa Legislature, is committed to making sure young Iowans know they belong in Iowa. After graduating from the University of Chicago in 2021, he moved back to Iowa.

“I think I got a world-class education at City High. I grew up around a lot of really incredible people, and a lot of them have left,” he said. “I heard people telling me they don’t see a future for themselves in this state.”

That’s why, in 2022, he decided to run for the Iowa House of Representatives.

“Look, it’s our future,” he said. “It impacts everyone in our state. If you’re an elderly person in Denison and you can’t find a home health aide, that’s a really big challenge. If you live in rural Southeast Iowa and you have to drive an hour and a half to give birth because there’s no OBGYN in your area, that’s also a big challenge.”

Effects of brain drain can also be seen in larger examples. Earlier this year, Hills Elementary School in Hills, Iowa, was closed because the Iowa City Community School District could not afford the cost per student. When people leave the state, schools close. Businesses close.

“[There’s a] workforce crisis. Talk to almost any small business and pretty much any field in the state and they’ll tell you they struggle to hire and find talent,” Zabner said. “It’s the fabric of our communities. Who’s here is really what this state is.”

Iowa is drowning in brain drain. But instead of fighting the problem and making people feel more welcome, the conservative government is polarizing Iowans, according to Zabner.

“We have to be a state that welcomes talent, [but] we’re pushing people away with some of these policies,” Zabner said. “Other states are actually competing to try and bring in talented people, so that puts us behind from the start.”

Zabner is a major proponent of targeted loan forgiveness and other ways of helping to keep college graduates in the state. Loan forgiveness programs would make college in Iowa much more accessible and the cost of living in Iowa would be lower, incentivizing young Iowans to live in Iowa. For Iowans who aren’t college educated, however, he also has ideas.

“We have to look at fighting to invest and create jobs in some of the fastest growing industries in the country,” Zabner said. “You see other states that have successfully built electrical vehicle plants, battery plants, and we could do a lot more on the economic development side to try and bring these types of jobs that are often high-paying and don’t require a college degree to Iowa.”

Iowa’s ability to recruit and retain citizens has an impact on everyone. Zabner believes that there are opportunities to become a major player in industries like renewable energy, but Iowa lacks the workforce and talent to make that happen.

At City High, students have the option to take iJAG, a two-year program where students learn about the workforce and different pathways they could follow after graduating from high school.

“I think a lot of young people don’t see a future where they have opportunities to grow in Iowa,” Lauren Whitehead, who teaches the iJAG program, said. “It seems like a dead end to some kids.”

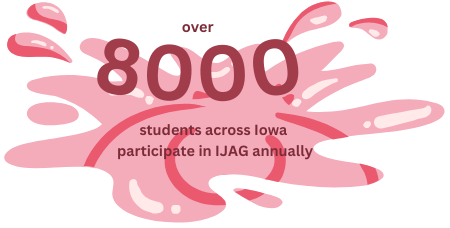

Iowa Jobs for America’s Graduates, or iJAG, is a statewide nonprofit that operates programs out of schools across the state. It focuses on preparing students for life after high school, whether or not students attend college. As part of the program, Whitehead brings in employers like the military and ALPLA (a manufacturer in Iowa City) in addition to a variety of two-year and four-year colleges.

“Our goal is to give students leadership opportunities, community service opportunities, meaningful engagement with their own future planning no matter what direction they plan to go,” Whitehead said.

Everything that iJAG does helps students prepare for life after graduation. Across the state, over 8,000 students in 174 programs take part in iJAG annually. Whitehead hopes that the program will help students see that they belong in Iowa and that they find their place here.

“When students really participate in [iJAG], they have opportunities to connect to amazing corporations in Iowa and be part of an alumni network. They build a lot of professional connections and connections are how you get jobs, right?” Whitehead said. “My hope is that iJAG creates that kind of supportive network so that when [students] go out into the world, they have some people there to catch them on the other side of graduation.”

More and more people are leaving Iowa. But with the right steps forward and the right preparation for students, Zabner believes that it will improve.

“There’s a fundamental promise that you want to live in a place where kids are going to be better off than their parents,” Zabner said. “But when I talk to younger folks in the state, I’m concerned that they’re not seeing that. It’s really sad to hear from folks whose aspiration is to find a way out of Iowa, when I think we could be doing a lot more to make those opportunities available right here in the state.”

—

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that there are no meteorology programs in Iowa. It has been corrected to accurately state that there is no meteorology program in Iowa City.

Maeve Clarke • Dec 23, 2024 at 7:56 am

Excellent piece about an important and timely topic- well done!