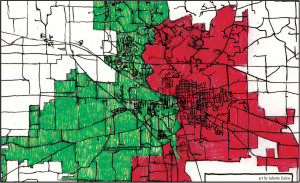

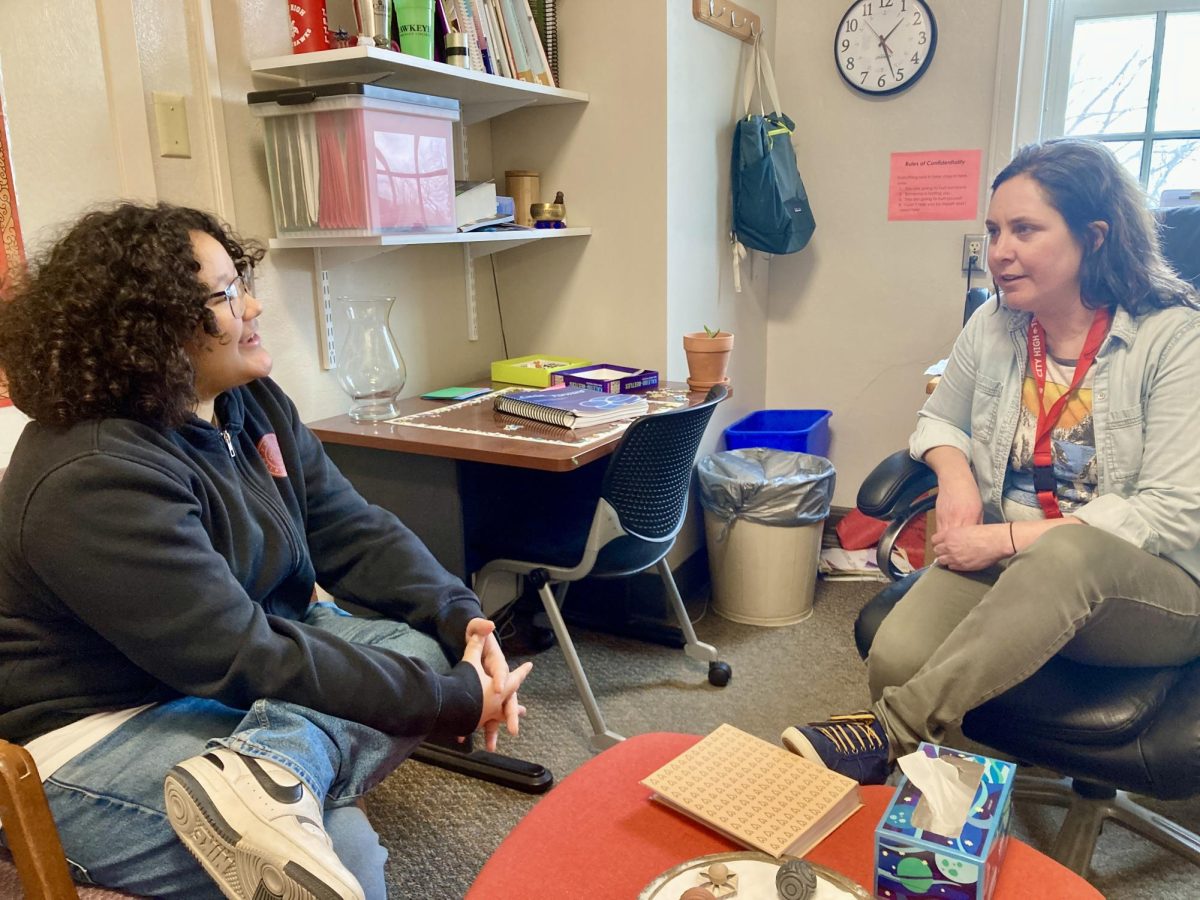

As the Iowa City Community School District Board gears up for a 2013 district-wide facilities plan, one of their top priorities is solving the problem of overcrowding in schools, and with 12,000 students and a divided constituency, there are no easy answers.

“This is certainly a very important time in our school district, as this board and the community try to chart a course for the future of our school district,” City High Principal John Bacon said. “And there’s no doubt there are some big decisions to be made right now.”

Stephen Murley, superintendent of schools for the Iowa City Community School District, is expected to publish a report early next year with his recommendations for the School Board, each of which will be discussed and voted on.

“We haven’t made any specific decisions,” board member Jeff McGinness, a local attorney, said. “[Superintendent Murley] is going to present us with a facilities plan. Throughout, we’re going to tweak it and come up with what the board wants as a district-wide facilities plan.”

With West High over capacity for the fifth year in a row, many fear that City will be unable to handle West’s surplus. One of the proposals before the board is a new, third comprehensive high school which the board has been saving up for since 2007 through the School Infrastructure Local Option (SILO) Sales Tax. Principal Bacon thinks the third-high-school option should be considered.

“Is there a way feasibly to stick with two [high schools]? That’s going to be more efficient and less expensive than building and operating a third high school,” Bacon said. “If we find that that would not work well, then I would certainly say that yes, it’s time to build another high school.”

McGinness is not sure if that need will arise any time soon.

“We have more pressing needs at the elementary level in the short term,” McGinness said. “So for me it would be to use the money we have for what we need right now, and then when we get to the point of saying we absolutely have to have this high school, then I’m for that.”

Julie Eisele is a mother of three ICCSD students and a backer of Support Iowa City Schools, a recently-formed group that opposes the construction of a new high school. She echoed McGinness’ concerns about addressing urgent needs first.

“There is nowhere to move elementary students right now on the East side, so there is a need for new elementary schools,” she said. “The most urgent needs are not at the high school level, because there is space at City High.”

Principal Bacon expressed a similar sentiment.

“I think it is really worth taking a serious look,” Bacon said, “at whether it’s time to put an elementary facility out here on the east side.”

He and others see new elementary schools both as a means of accommodating existing students as well as creating growth.

“I think you’re seeing people in the older parts of town say, ‘hey, a lot of the new building is there [on the west side],” Bacon said. “Schools are built because those areas are growing, but then once they’re built and there’s this beautiful new school there, it is a little bit of, ‘if you build it, they will come.’”

Some maintain that instead of building new schools, balance can be restored to schools simply by redrawing zoning lines. Chip Hardesty, a monitor and coach at City High, said the board has been unwilling to “take the political heat for it,” referring to resistance from families to switching school zones.

“It’s a sad belief that kids can’t adapt,” Tom Yates, president of the Iowa City teachers’ union, Iowa City Education Association, said. “How long does it take a little kid to make new friends?”

Such concerns came to light dramatically in 2009. That was the year the board began the process of comprehensive redistricting, a process that Tuyet Dorau, another board member, says started a dialogue that “could be very ugly.”

“It started up talking about things that we were not always comfortable talking about,” Dorau said.

Many students from areas that had long fed to West were reassigned to City, and at town meetings and other forums, families expressed criticism of City and doubts about their children’s ability to thrive there.

“I think that people fear change,” Eisele said. “They have allegiances to certain high schools and it makes sense that they do because…boundaries have not changed for forty years.”

Board members are eager to get past these allegiances.

“I have problems with ‘us’ and ‘them,’” Karla Cook, a former City High math teacher and current board member, said. “Every school in this district is a good school and saying that one is better than another one — it bothers me.”

The board should look deeper than numbers, according to some. Hardesty looks to the board to “balance so-called socio-economic levels of students,” but, he specified, “not necessarily based along more traditional diversity lines like race.”

“That’s a pet peeve of mine,” he added. “That’s a shallow definition of diversity.”

Hardesty also joins many others in his disappointment with the results of the board’s 2009 decisions, which suffered from a lack of enforcement, as well as grandfathering clauses, which Cook admitted “caused some problems.” Hardesty went as far as to say that “all the redistricting in 2009” accomplished “virtually nothing.”

“The delays and accommodations built into that system have meant that it’s been years before we even start to see some of that,” Hardesty said.

Yates does not think the 2009 decision-making process was handled well.

“Nothing got acted on. One of the strangest things about the process was the one hundred thousand plus dollars the district spent on the consulting firm from Kansas City which basically provided demographic information the district already had,” he said. “And then nothing happened.”

Doreau explained that, due to “two or three rounds of grandfathering,” it will be two to three years before the district “start[s] seeing the results and repercussions of those moves.”

Dissatisfaction with the School Board is attributed by some community members to deeper flaws in the board’s functioning, specifically their lack of a long-term plan or a more regular redistricting schedule. According to McGinness, such deficiencies have led to a board that is “always playing from behind.”

“We don’t really have a comprehensive facilities plan,” McGinness said.

Yates agreed. “Other districts at least have a process in place whereby they can look at redistricting issues… every three years or every fives years,” Yates said.

Others go even further, maintaining that in the Board’s focus on redistricting, they have neglected important issues.

“We’ve been focusing on field turf. We’ve been focusing on selling Roosevelt. We’ve been focusing on building an elementary, without data,” Dorau said. “Instead of talking about managing things, we should have been talking about what do we want to accomplish as far as priorities for our district when it comes to education.”

Cook echoed this sentiment: “I wonder when it is that we’re going to start talking about what we teach and how we teach it, because I honestly think that the classroom teacher and the curriculum are the most important thing for a student.”

The school board understands that whatever is decided next year, their work will not be over.

“When we are dealing with a pot of money that isn’t large enough to do everything we want or need to do, we’re never going to make everybody happy,” McGinness said. “And there has to be some compromise.”

Despite the challenges, the board is not ready to stop wrestling with the tough questions of education.

“You guys are going to be the ones that revolutionize the world,” Dorau said, addressing the district’s students. “So are we giving you what you need?”

![ICCSD School District Map [art by Juliette Enloe]](https://www.thelittlehawk.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Redistricting-Map-1024x626.jpg)